It took me some years to get comfortable with the idea that I could adjust patterns. Seems silly in retrospect since sewing offers the promise of making things fit better. And of course the truth is that I did make adjustments. But very simple ones. The most obvious being that I would lengthen trouser legs and often adjust the tapering of the leg seam, I tend to like pants that are closer to drain pipes than palazzo. Here I want to talk about two more significant adjustments that are now fairly routine for me.

Note: in order to decide to do an adjustment I make a version following the instructions and cutting out the template as the pattern designer designed it. In the world of sewing this is often called a muslin, and was made in muslin fabric. I never make a muslin in muslin fabric, I buy and use cheap wovens and knits instead.

Lowering Normal Darts

Most patterns, even indie patterns, seem to be designed for a younger woman. As I’ve aged, so my boobs have lowered (proof of gravity I like to think). I believe this is relatively common. Anyway, if the darts in any pattern are going to come to the full apex of my bust they have to be moved down to meet me where I’m at.

There’s been many a blog post written and many a YouTube video made on how to do this for normal darts. Good terms to Google on are “lowering darts.” The gist is pretty simple. You measure the distance between where the dart on the pattern lands on your body and the actual place where the fullest part of your bust is. Say, that your bust is about an 1inch lower. Then you simply move the dart by making a box around it and lowering it. This involves cutting it out of the pattern piece and reinserting it at the lower point. Then you smooth the side seams out.

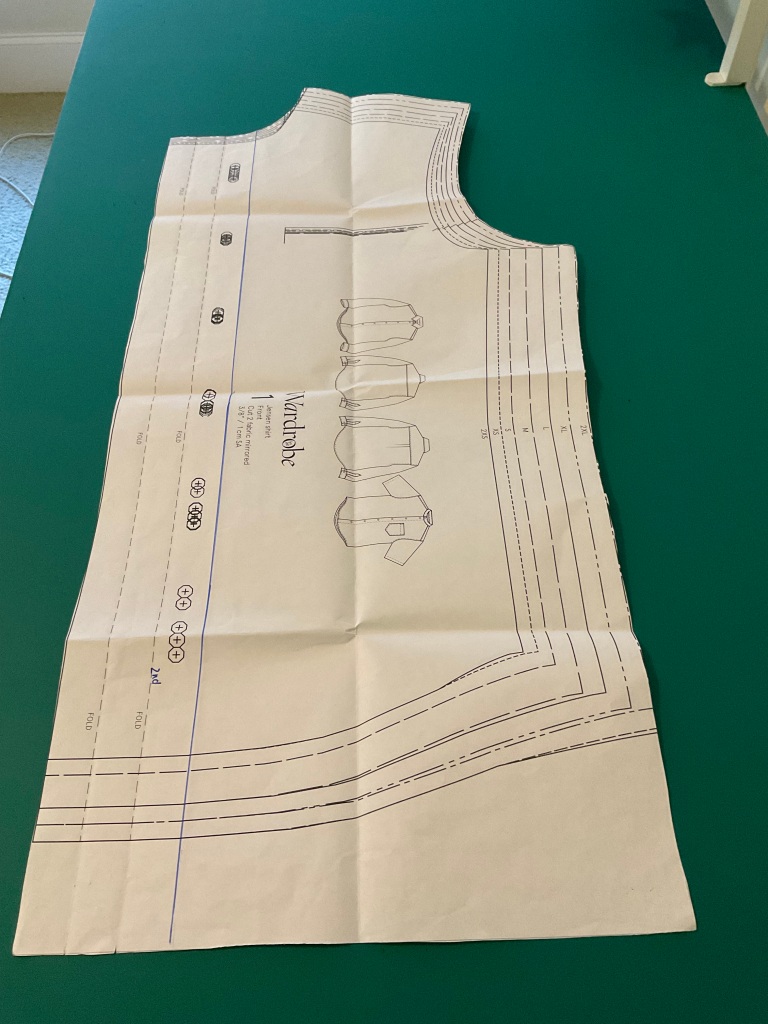

And this is what that looks like on my pattern. The box I cut around my dart and how I added room at the top of the box (the all white box) and how the box now covers some of the pattern at the bottom.

What About French Darts?

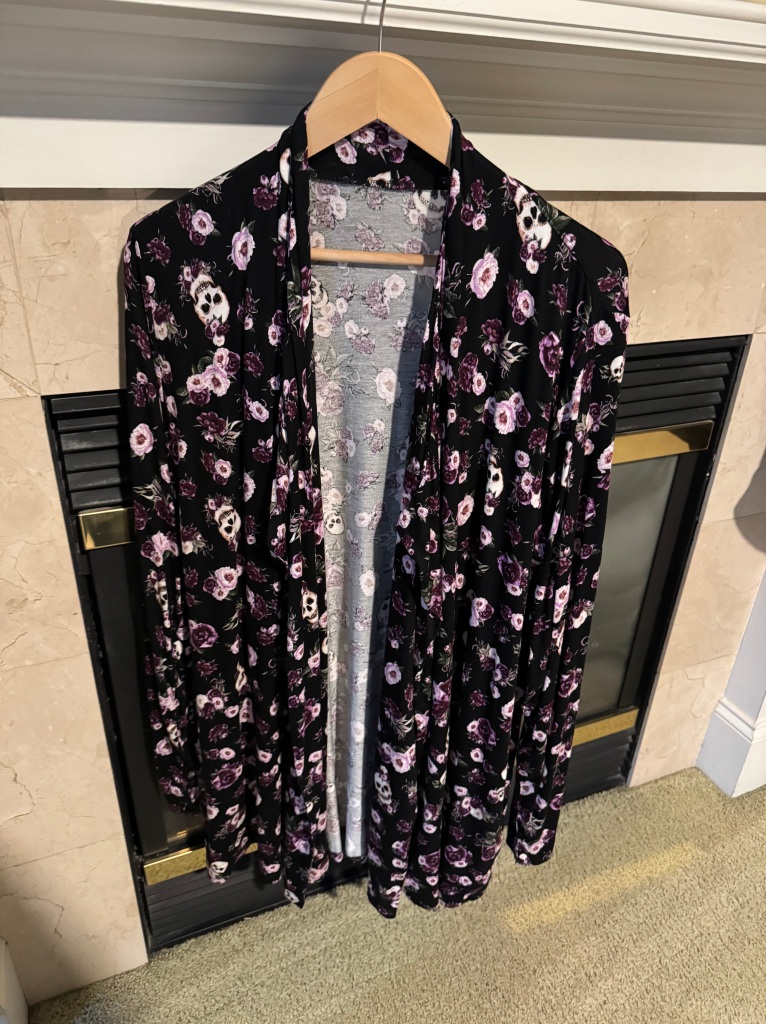

I wondered for a long time whether the principle was the same with a French Dart. A French Dart is a much bigger dart, it has a longer length and covers (in a diagonal) a much larger part of the pattern. A good example of the French Dart is the French Dart Shift by Maven Patterns. I love this pattern. It’s a lovely make and I’ve made it in both the woven fabrics that the pattern was designed for and knits as a tutorial suggested in the pattern hacks. (Shout out to Indie makers who provide these kinds of hacks, it’s a great way to get started in customizing a pattern, take someone else’s recommendations for switching it up. I honestly think it gave me the confidence to do more of my own).

I looked everywhere for French Dart adjustments and like Untitled Thoughts I couldn’t find much. Her post is a very detailed essay on how she altered a French Dart on her dress pattern. I have to admit I was intimidated. Then I decided to write to Mrs. Maven, the designer/owner of Maven Patterns. She wrote back very quickly (another shout out to the Indie Pattern companies I’ve written too and their kind and quick replies). She basically told me that I should use the same method I’d used for a normal dart!

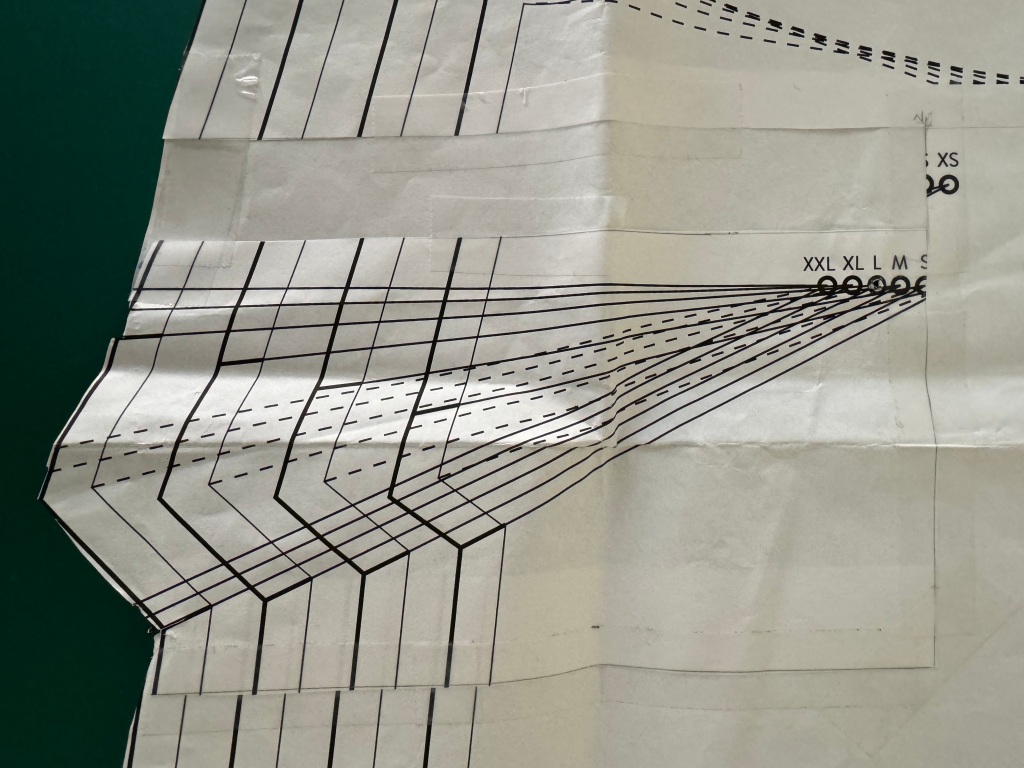

And so I did. Here it is on my pattern. As you can see gravity had really done a number on where my dart needed to be, so this is about 2 inches lower. But it’s exactly the same principle just with a much larger box. But there’s one wrinkle, look to the bottom and you’ll see that there are notch markings for pockets. French Darts get much closer to the waist area, so they begin to interact with the pockets.

What to do about my pockets, because I certainly didn’t want to get rid of my pockets. Initially I thought I shouldn’t lower those too because the designer had put them there for a reason. But then I paused and two thoughts emerged. First, I could put the pockets where the French Dart ended, in other words they could overlap. The purpose of the dart is to create shaping in the bust area of the garment. At the side seam it functions just like a side seam although there is some extra bulk (e.g., the seams of the dart legs). So maybe that would matter on some fabrics but maybe it wouldn’t.

Second, why couldn’t I also move the pockets. In my case that turned out to be a winning idea. Turns out that my boobs are not the only part of my body that is non-custom. It turned out that lowering the pockets worked for me. It is now the case that the pockets on my version of the French Dart shift begin right after the new lowered French Dart.

In summary, I lowered the French Dart using the method suggested for normal darts and also lowered the pockets.