Federal courts have limited the Biden administration’s authority to set nationwide standards regulating emissions from power plants. But some cities and states are pushing to meet stringent climate goals by other means. In October, the Hawaii Supreme Court allowed the city and county of Honolulu, along with the local water utility board, to claim that oil and gas companies failed to disclose the risks their products posed to the environment. As a result, the suit alleges, buyers overconsumed oil and gas, which caused excess emissions, which increased global temperatures, which caused sea levels to rise, which then damaged Honolulu.

The energy companies are now asking the U.S. Supreme Court to put a stop to this charade. It should, for several reasons.

Jeff Jacoby warns of the dangerous precedent Biden is setting by defying – and boastfully so – the U.S. Supreme Court. Two slices:

EVER SINCE the Supreme Court ruled last year that President Biden had no authority to unilaterally write off $430 billion in student loans, he and his aides have been crowing that they intended to do it anyway.

Within hours of the court’s decision, Biden truculently told reporters that the court was wrong. He declared he would “stop at nothing to find other ways” to get what he wanted. Soon the administration began generating fresh schemes to cancel student debt — or, more accurately, to transfer that debt to taxpayers. In February, announcing his intention to relieve an additional 153,000 borrowers of the obligation to pay back what they owe, Biden again stressed that he would not comply with the court’s mandate. “The Supreme Court blocked it, but that didn’t stop me,” he boasted on Feb. 21.

Last Monday came another White House move to wipe out student loans — this time absolving some 30 million individuals of their liabilities. Once more there was an explicit assertion of resistance to the court’s decision. “When the Supreme Court struck down the president’s boldest student debt relief plan,” Education Secretary Miguel Cardona proclaimed, “within hours we said: ‘We won’t be deterred.'”

…..

Either way, Biden’s open snub of the Supreme Court is pushing the rule of lawlessness to a dangerous new level. As he campaigns against Trump in this year’s election, the president keeps warning that America’s democratic values are in jeopardy. He’s right. But as his refusal to abide by an unambiguous decision of the nation’s highest court shows, his opponent isn’t the only candidate jeopardizing them.

Thomas Feddo warns of Biden’s reckless pandering to labor unions and the economically ignorant. A slice:

President Biden weighed in last month on Nippon Steel’s proposed acquisition of U.S. Steel. “It is vital,” he said in a statement, for the latter “to remain an American steel company that is domestically owned and operated.” Soon after, the United Steelworkers endorsed the president. This may be an empty election-year promise. If it isn’t, it’s a pledge to subvert the law and cripple a vital national-security tool in the process.

The only obvious way to stop the acquisition is through the Committee on Foreign Investment in the U.S., or Cfius, a nearly 50-year-old interagency panel that scrutinizes cross-border deals to determine whether they could harm national security. The two steel companies had filed for Cfius review a week before the president’s statement.

Cfius is composed of nine cabinet officials and led by the Treasury secretary. Its work is confidential, rigorous and fact-based, and its statutory remit concerns only national security. Congress mandates Cfius conduct its analysis in secret and precludes the president from dictating its decisions. Mr. Biden’s statement didn’t mention Cfius or national security, but it’s reasonable to suspect he hoped to influence the committee.

But an adverse ruling from Cfius would clearly be improper.

Speaking of Biden, these letters in today’s Wall Street Journal are spot-on. Here’s one:

Why are student loans more deserving of forgiveness than any other kind of debt? (“Biden’s Latest Lawless Debt Forgiveness,” Review & Outlook, April 9). President Biden hasn’t proposed paying off everybody’s mortgage or car loan—yet. If, after canceling student loans, he wants to buy still more votes with other people’s money, that will be an option. Don’t think he wouldn’t consider it.

Keith E. Smith

Silver Spring, Md.

Here’s my intrepid Mercatus Center colleague, Veronique de Rugy, on inflation.

What’s troubling today is the new ideology that’s taken over newsrooms during the Trump years. Journalism is now focused more on political correctness and political point scoring than on traditional journalistic ethics like fairness, independence and truth-seeking. It enforces a rigid orthodoxy that promotes specific viewpoints while shutting out other voices that don’t stick to the approved narrative. In short, the news today tells its readers, viewers and listeners what to think.

James Pethokoukis unfailingly writes wisely about innovation.

During their meeting the two “agreed on the need for free markets and defend the ideas of freedom,” the Argentine government said in a statement. “The President and the businessman spoke in Texas about the importance of eliminating bureaucratic obstacles that keep investors away,” it added.

Kimberlee Josephson explains how today’s business schools often undermine wealth creation.

GMU Econ alum Jayme Leake reviews Jessamine Chan’s dystopian 2022 novel, The School for Good Mothers.

It pays to have friends in high places. (HT Todd Zywicki)

Robert Frank once reported being baffled that I would reject modest redistribution from rich to poor. Amartya Sen intervened at that moment and told Bob he needed to listen. Affluent scholars see a pie and see how they want to slice it, but Sen saw me starting in a different place – with the truism that power corrupts. Starting from that truism, what is baffling is that anyone could so cavalierly endorse concentrated power when we live in a world where concentrated power is so often used to redistribute not from rich to poor but from poor to rich. Sen went on to say that when it comes to inequality, the question is not whether we can find a statistic that gives credence to the resentment the richest scholars feel as the richest movie stars leave them behind, but which dimensions of rising inequality do poor people care about?

Robert Frank once reported being baffled that I would reject modest redistribution from rich to poor. Amartya Sen intervened at that moment and told Bob he needed to listen. Affluent scholars see a pie and see how they want to slice it, but Sen saw me starting in a different place – with the truism that power corrupts. Starting from that truism, what is baffling is that anyone could so cavalierly endorse concentrated power when we live in a world where concentrated power is so often used to redistribute not from rich to poor but from poor to rich. Sen went on to say that when it comes to inequality, the question is not whether we can find a statistic that gives credence to the resentment the richest scholars feel as the richest movie stars leave them behind, but which dimensions of rising inequality do poor people care about? And so I insist that collectivism, which replaces the free market by coercive centralized authority, is reactionary in the exact sense of the word. Collectivism not only renders impossible the progressive division of labor, but requires, wherever it is attempted, a regression to a more primitive mode of production.

And so I insist that collectivism, which replaces the free market by coercive centralized authority, is reactionary in the exact sense of the word. Collectivism not only renders impossible the progressive division of labor, but requires, wherever it is attempted, a regression to a more primitive mode of production. It is the great merit of democracy that the demand for the cure of a widely felt evil can find expression in an organized movement. That popular pressure might become canalized in support of particular theories that sound plausible to the ordinary man is one of its dangers.

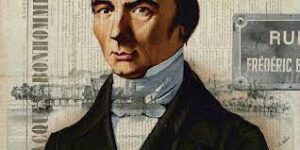

It is the great merit of democracy that the demand for the cure of a widely felt evil can find expression in an organized movement. That popular pressure might become canalized in support of particular theories that sound plausible to the ordinary man is one of its dangers. History has yet to produce a foe of protectionism who is at once as skilled, as sharp, as logical, as consistent, as gripping, as unrelenting, as informed, as indomitable, as astute, and as entertaining as was Frédéric Bastiat. And while it’s folly to try to single out any one essay of Bastiat’s that is most effective at exposing the idiocy of protectionism, at least it’s possible – and worthwhile – to highlight a few of his essays that deserve special attention. Today I highlight Bastiat’s December 1847 essay “L’indiscret,” translated into English by David Hart as “

History has yet to produce a foe of protectionism who is at once as skilled, as sharp, as logical, as consistent, as gripping, as unrelenting, as informed, as indomitable, as astute, and as entertaining as was Frédéric Bastiat. And while it’s folly to try to single out any one essay of Bastiat’s that is most effective at exposing the idiocy of protectionism, at least it’s possible – and worthwhile – to highlight a few of his essays that deserve special attention. Today I highlight Bastiat’s December 1847 essay “L’indiscret,” translated into English by David Hart as “