Ron Bailey warns that a Greenpeace initiative “will blind and kill children.” A slice:

Greenpeace and other anti-biotech activist groups have logged a win in a crusade that could ultimately blind and kill thousands of children annually. How? By persuading the Court of Appeals of the Philippines to issue a scientifically ignorant and morally hideous decision to ban the planting of vitamin A–enriched golden rice. The objective result will be more children blinded and killed by vitamin A deficiency.

David Henderson is no fan of minimum-wage diktats. A slice:

Moreover, if monopsony does exist, it, by definition, must be regional in nature. You can’t have an employer in, say, high-wage San Francisco having monopsony power over labor in, say, lower-wage Bakersfield. That means that if monopsony is the justification, the minimum wage to offset it should be set for a region rather than a large state: San Francisco should have its high minimum wage and Bakersfield should have its lower minimum wage. So ixnay on a California fast-food wage.

One of the leading proponents of the idea of monopsony in the labor market is British economist Alan Manning of the London School of Economics. He and I debated the minimum wage in an event sponsored by a group of MBA students at Northwestern University. In that debate, Manning claimed that even a large increase in the US minimum wage would cause little or no job loss.

He gave this example to make his case. See if you can spot his implicit, and implausible, assumption. An employer has an employee who produces something worth $12 an hour to the employer. The employer currently pays the employee $8 an hour. So, if the government raises the minimum wage to $10 an hour, the employer will continue to hire the worker. That’s true.

But did you catch his implicit assumption, which is almost certainly false? Here it is. Manning assumed that employers aren’t competing for workers. But if another employer also can hire the worker to produce something worth $12 an hour, why wouldn’t he offer, say, $9 and still make a lot of money on the employee? Then another employer would offer $10. Et cetera. Competition would drive the employee’s wage up close to the value of what he produces. It might not be $12 because the employee has some cost of moving. But it’s likely to be much closer to $12 than to $8. And that means there’s a very thin zone in which to raise the minimum wage and not cause job loss.

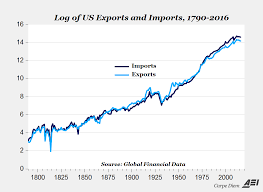

Scott Lincicome is correct: “The global economy is far more dynamic—and resilient—than you think.” Two slices:

The day after the accident, for example, the New York Times’ Peter Goodman proclaimed that the “wayward container ship” yet again “shows world trade’s fragility”—and thus serves as a highly visible example of “the pitfalls of relying on factories across oceans to supply everyday items like clothing and critical wares like medical devices.” His NYT colleague Paul Krugman was less hysterical but nevertheless wrote a week later that, “Supply chains are making me nervous again” and warned of broader economic harm. The Washington Post dinged the accident as a result and symbol of “rampant globalization” and openly worried about these disruptions causing “big problems” economically. These outlets certainly weren’t alone in their worry. And social media, as you can imagine, went even further.

…..

The warnings proved hollow because they assumed that the Port of Baltimore’s billions in economic activity would simply cease in the days and weeks following the bridge accident. Yet mere hours after the Key Bridge collapsed on March 26, shipping companies and supply chain professionals began adjusting their operations to minimize the disruption. The very next morning, for example, ships headed for Baltimore had already started to arrive at alternative ports along the eastern seaboard—ports that subsequently expanded hours and made other operational changes to accommodate the additional cargo (including for all those automobiles).

Columbia University alum Bob Graboyes understandably now loathes his alma mater. A slice:

Use the wrong pronoun or wear a sombrero on Cinco de Mayo, and your university will consider bringing out the firehoses and German shepherds; but assault Jewish students and call for their extermination (along with the eradication of a sovereign nation), and the same university will defend your actions as representing the sacred right to free and open speech. Antisemitism has spread like ebola across American Academia.

Peter Earle and Thomas Savidge argue for removing government from GDP.

Juliette Sellgren talks with Russ Sobel about entrepreneurship.

George Will makes the case for U.S. aid to Ukraine.

Wall Street Journal columnist James Freeman isn’t a fan of NPR’s new CEO, Katherine Maher.

Several recent studies have found evidence that minimum wage increases change hiring patterns, as higher-skilled workers tend to replace lower-skilled workers. A

Several recent studies have found evidence that minimum wage increases change hiring patterns, as higher-skilled workers tend to replace lower-skilled workers. A  Commodity money evolved as naturally and as spontaneously as the wheel, the screw, the hydraulic press, the inclined plane, a national language, and common law. Its emergence was economic and natural, not political and contrived.

Commodity money evolved as naturally and as spontaneously as the wheel, the screw, the hydraulic press, the inclined plane, a national language, and common law. Its emergence was economic and natural, not political and contrived. But, shockingly, against all this apparent common sense and ethical appeal, the labor theory of value is wholly mistaken as a matter of economics. It’s deeply screwy, scientifically, and evil in its ethics.

But, shockingly, against all this apparent common sense and ethical appeal, the labor theory of value is wholly mistaken as a matter of economics. It’s deeply screwy, scientifically, and evil in its ethics. Exports and imports are inherently interdependent, and any policy that reduces one will also reduce the other.

Exports and imports are inherently interdependent, and any policy that reduces one will also reduce the other.