The moon rose over the bay. I had a lot of feelings.

I am taken with the hot animal

of my skin, grateful to swing my limbs

and have them move as I intend, though

my knee, though my shoulder, though something

is torn or tearing. Today, a dozen squid, dead

on the harbor beach: one mostly buried,

one with skin empty as a shell and hollow

feeling, and, though the tentacles look soft,

I do not touch them. I imagine they

were startled to find themselves in the sun.

I imagine the tide simply went out

without them. I imagine they cannot

feel the black flies charting the raised hills

of their eyes. I write my name in the sand:

Donika Kelly. I watch eighteen seagulls

skim the sandbar and lift low in the sky.

I pick up a pebble that looks like a green egg.

To the ditch lily I say I am in love.

To the Jeep parked haphazardly on the narrow

street I am in love. To the roses, white

petals rimmed brown, to the yellow lined

pavement, to the house trimmed in gold I am

in love. I shout with the rough calculus

of walking. Just let me find my way back,

let me move like a tide come in.

by Donika Kelly

from Academy of American poets, 11/20/2017

Copyright © 2017

Will you please consider becoming a supporter of 3QD by clicking here now? We wouldn’t ask for your support if we did not need it to keep the site running. And, of course, you will get the added benefit of no longer seeing any distracting ads on the site. Thank you!

Will you please consider becoming a supporter of 3QD by clicking here now? We wouldn’t ask for your support if we did not need it to keep the site running. And, of course, you will get the added benefit of no longer seeing any distracting ads on the site. Thank you!

Years ago, for reasons I still don’t fully understand, I found myself writing about flight. It started as just a few paragraphs, a bit of spontaneous fiction jotted down in a notebook: a man stood on the roof of a barn, wearing a pair of enormous wings built from wood and cloth. His friend on the ground—the narrator—looked on nervously, ready to call an ambulance. And then the man jumped. Somehow, he flew.

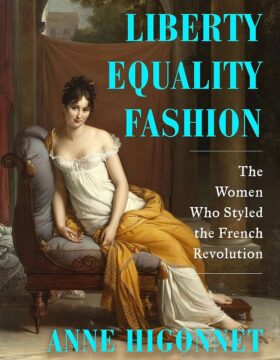

Years ago, for reasons I still don’t fully understand, I found myself writing about flight. It started as just a few paragraphs, a bit of spontaneous fiction jotted down in a notebook: a man stood on the roof of a barn, wearing a pair of enormous wings built from wood and cloth. His friend on the ground—the narrator—looked on nervously, ready to call an ambulance. And then the man jumped. Somehow, he flew. After they were released from prison in Paris in the late autumn of 1794, both having narrowly escaped the guillotine, new bosom friends Rose de Beauharnais and Térézia Tallien found they had nothing to wear. Dressmakers and milliners had all but disappeared from a city still reeling from the Reign of Terror. In an era of desperate need and rampant inflation, a time when even the most prosperous took candles and bread with them when they went out to dinner, who could afford a silk dress, still less stays, hoops, acres of petticoats and several maids to sew you into it?

After they were released from prison in Paris in the late autumn of 1794, both having narrowly escaped the guillotine, new bosom friends Rose de Beauharnais and Térézia Tallien found they had nothing to wear. Dressmakers and milliners had all but disappeared from a city still reeling from the Reign of Terror. In an era of desperate need and rampant inflation, a time when even the most prosperous took candles and bread with them when they went out to dinner, who could afford a silk dress, still less stays, hoops, acres of petticoats and several maids to sew you into it? ‘At a quarter to eleven on August 12, 2022, on a sunny Friday morning in upstate New York, I was attacked and almost killed by a young man with a knife,” begins Salman Rushdie’s new memoir.

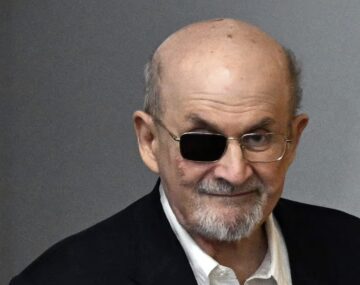

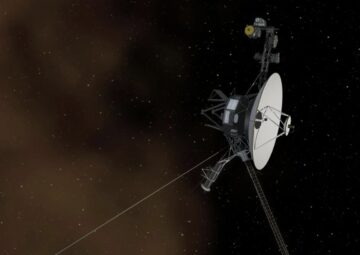

‘At a quarter to eleven on August 12, 2022, on a sunny Friday morning in upstate New York, I was attacked and almost killed by a young man with a knife,” begins Salman Rushdie’s new memoir. NASA’s interstellar explorer Voyager 1 is finally communicating with ground control in an understandable way again. On Saturday (April 20), Voyager 1 updated ground control about its health status for the first time in 5 months. While the

NASA’s interstellar explorer Voyager 1 is finally communicating with ground control in an understandable way again. On Saturday (April 20), Voyager 1 updated ground control about its health status for the first time in 5 months. While the  Kwame Anthony Appiah is a British-Ghanaian philosopher, Professor of Philosophy and Law and New York University, and the “Ethicist” columnist for The New York Times Magazine.

Kwame Anthony Appiah is a British-Ghanaian philosopher, Professor of Philosophy and Law and New York University, and the “Ethicist” columnist for The New York Times Magazine. “Where is Ahmad?” The soldier called my name while we were stopped at the last Israeli checkpoint on the way from Ramallah to Jerusalem. I am a Palestinian American. But once I’m in my ancestral homeland, I’m not an American in the eyes of Israeli authorities. I am simply Palestinian, denied the basic right to movement and pilgrimage to the Holy Land. For too long, Palestinians in the diaspora, like myself, became travelers on our soil. We tried to forget the realities of occupation in the West Bank, and that a few hours south in Gaza our brothers and sisters suffered under even more

“Where is Ahmad?” The soldier called my name while we were stopped at the last Israeli checkpoint on the way from Ramallah to Jerusalem. I am a Palestinian American. But once I’m in my ancestral homeland, I’m not an American in the eyes of Israeli authorities. I am simply Palestinian, denied the basic right to movement and pilgrimage to the Holy Land. For too long, Palestinians in the diaspora, like myself, became travelers on our soil. We tried to forget the realities of occupation in the West Bank, and that a few hours south in Gaza our brothers and sisters suffered under even more  If you put a lab mouse on a diet, cutting the animal’s caloric intake by 30 to 40 percent, it will live, on average, about 30 percent longer. The calorie restriction, as the intervention is technically called, can’t be so extreme that the animal is malnourished, but it should be aggressive enough to trigger some key biological changes. Scientists

If you put a lab mouse on a diet, cutting the animal’s caloric intake by 30 to 40 percent, it will live, on average, about 30 percent longer. The calorie restriction, as the intervention is technically called, can’t be so extreme that the animal is malnourished, but it should be aggressive enough to trigger some key biological changes. Scientists  Kant’s views here are taken by many philosophers to be an impossible attempt to have it both ways. Kant seems to be arguing that evil is necessarily attributed to each of us, apparently rooted in human nature. And yet at the same time he claims that evil is freely chosen: each of us is fully responsible for this unavoidable human predicament. But how is this possible? How could a condition “entwined with humanity itself” be something that “come[s] about through one’s own fault”?

Kant’s views here are taken by many philosophers to be an impossible attempt to have it both ways. Kant seems to be arguing that evil is necessarily attributed to each of us, apparently rooted in human nature. And yet at the same time he claims that evil is freely chosen: each of us is fully responsible for this unavoidable human predicament. But how is this possible? How could a condition “entwined with humanity itself” be something that “come[s] about through one’s own fault”? Today, Le Samouraï is recognized as a foundational example of neo-noir, and as a spark that lit a fire under Scorsese, Mann, Tarantino, Jarmusch, Woo, Fincher, et al.—see Taxi Driver (1976), Thief (1981), Reservoir Dogs (1992), Ghost Dog (1999), The Killer (1989), and The Killer (2023). Even the Matrix and John Wick franchises are suffused with references to its cult mythology: aloof antiheroes with sharp suits and slick autos pursued on all sides as they stalk through moody cityscapes, inescapably hurtling toward the violent resolution of their own personal destiny? Check. Such respect and veneration from his American and international peers was something the Stetson- and Ray-Ban-sporting Melville, who functioned as something of a godfather to Jean-Luc Godard and the nascent French New Wave, would have been pleased to receive. Unfortunately, his own dramatic personal destiny was to intervene. In 1973, at only fifty-five, the filmmaker suffered a fatal heart attack over lunch while discussing his next picture—a spy thriller set to star Yves Montand and Catherine Deneuve, never to witness the explosive chain reaction in mainstream cinema that his unapologetic, maverick methods had set off.

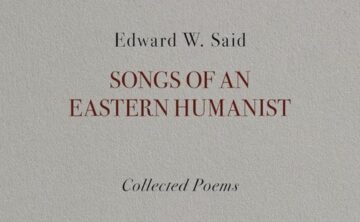

Today, Le Samouraï is recognized as a foundational example of neo-noir, and as a spark that lit a fire under Scorsese, Mann, Tarantino, Jarmusch, Woo, Fincher, et al.—see Taxi Driver (1976), Thief (1981), Reservoir Dogs (1992), Ghost Dog (1999), The Killer (1989), and The Killer (2023). Even the Matrix and John Wick franchises are suffused with references to its cult mythology: aloof antiheroes with sharp suits and slick autos pursued on all sides as they stalk through moody cityscapes, inescapably hurtling toward the violent resolution of their own personal destiny? Check. Such respect and veneration from his American and international peers was something the Stetson- and Ray-Ban-sporting Melville, who functioned as something of a godfather to Jean-Luc Godard and the nascent French New Wave, would have been pleased to receive. Unfortunately, his own dramatic personal destiny was to intervene. In 1973, at only fifty-five, the filmmaker suffered a fatal heart attack over lunch while discussing his next picture—a spy thriller set to star Yves Montand and Catherine Deneuve, never to witness the explosive chain reaction in mainstream cinema that his unapologetic, maverick methods had set off. IN OUT OF PLACE: A Memoir (1999), Edward Said recalls that after graduating from Princeton in June 1957, he was torn by “differing impulses”: he could pursue a fellowship from Harvard for graduate study or return to Cairo to work at his father’s stationery company. Eventually, Said deferred Harvard for a year and returned to “sample the Cairo life.” Said claimed that he had no interest in his father’s business, and in the memoir, he recalls how he spent his afternoons in his father’s office: “I would either read—I remember I spent a week reading all through Auden, another leafing through the Pléiade edition of Alain […]—or I would write poetry (some of which I published in Beirut), music criticism, or letters to various friends.” Two decades after Said’s death, we finally have access to 19 of these poems, written between 1956 and 1968, which have been compiled and edited by his biographer, Timothy Brennan, as Songs of an Eastern Humanist (2024).

IN OUT OF PLACE: A Memoir (1999), Edward Said recalls that after graduating from Princeton in June 1957, he was torn by “differing impulses”: he could pursue a fellowship from Harvard for graduate study or return to Cairo to work at his father’s stationery company. Eventually, Said deferred Harvard for a year and returned to “sample the Cairo life.” Said claimed that he had no interest in his father’s business, and in the memoir, he recalls how he spent his afternoons in his father’s office: “I would either read—I remember I spent a week reading all through Auden, another leafing through the Pléiade edition of Alain […]—or I would write poetry (some of which I published in Beirut), music criticism, or letters to various friends.” Two decades after Said’s death, we finally have access to 19 of these poems, written between 1956 and 1968, which have been compiled and edited by his biographer, Timothy Brennan, as Songs of an Eastern Humanist (2024). In 2022, researchers at the Bee Sensory and Behavioral Ecology Lab at Queen Mary University of London observed bumblebees doing something remarkable: The diminutive, fuzzy creatures were engaging in activity that

In 2022, researchers at the Bee Sensory and Behavioral Ecology Lab at Queen Mary University of London observed bumblebees doing something remarkable: The diminutive, fuzzy creatures were engaging in activity that  That a popular candidate could be disqualified from running and removed from the ballot might, at first glance, seem at odds with the very idea of democracy. For that reason, despite his evident role in instigating an insurrection, many Republican senators demurred and chose not to impeach former President Donald J. Trump on 13 January 2021. There was no need, they thought. The American voters had already passed judgment. Trump would now fade away.

That a popular candidate could be disqualified from running and removed from the ballot might, at first glance, seem at odds with the very idea of democracy. For that reason, despite his evident role in instigating an insurrection, many Republican senators demurred and chose not to impeach former President Donald J. Trump on 13 January 2021. There was no need, they thought. The American voters had already passed judgment. Trump would now fade away. ‘Philosophical theories are much more like good stories than scientific explanations.’ This provocative remark comes from the paper ‘Linguistic Philosophy and Perception’ (1953) by Margaret Macdonald. Macdonald was a figure at the institutional heart of British philosophy in the mid-

‘Philosophical theories are much more like good stories than scientific explanations.’ This provocative remark comes from the paper ‘Linguistic Philosophy and Perception’ (1953) by Margaret Macdonald. Macdonald was a figure at the institutional heart of British philosophy in the mid- How the brain processes visual information — and its perception of time — is heavily influenced by what we’re looking at, a study has found. In the experiment, participants perceived the amount of time they had spent looking at an image differently depending on how large, cluttered or memorable the contents of the picture were. They were also more likely to remember images that they thought they had viewed for longer. The findings, published on 22 April in Nature Human Behaviour

How the brain processes visual information — and its perception of time — is heavily influenced by what we’re looking at, a study has found. In the experiment, participants perceived the amount of time they had spent looking at an image differently depending on how large, cluttered or memorable the contents of the picture were. They were also more likely to remember images that they thought they had viewed for longer. The findings, published on 22 April in Nature Human Behaviour