More Tuesday links

1. AI Camera turns your images into poetry.

2. Highly capable model locally on your phone.

3. Clara Piano reviews GOAT. “Perhaps, in his emphasis on the importance of ideas, Cowen reveals that he is ultimately a Simonian. After all, the human mind is the ultimate resource.”

4. Market liberalism, Chinese style.

5. Red flags for improper judicial conduct.

6. Data on the economics of bookselling, designed to dissuade would-be authors.

Four Thousand Years of Egyptian Women Pictured

In an excellent, deep-dive Alice Evans looks at patriarchy in Egypt using pictures drawn from four thousand years of history. Here are three examples.

In an excellent, deep-dive Alice Evans looks at patriarchy in Egypt using pictures drawn from four thousand years of history. Here are three examples.

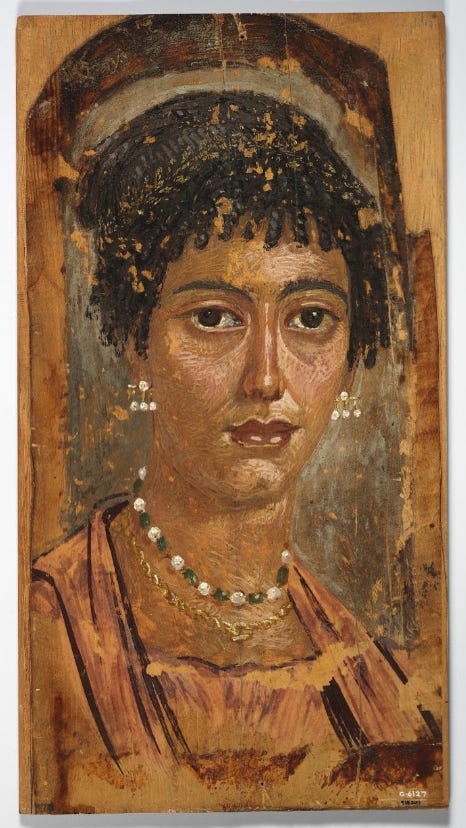

A wealthy woman, shown at right circa 116 CE. Unveiled, immodest, looking out at the world. A person to be reckoned with.

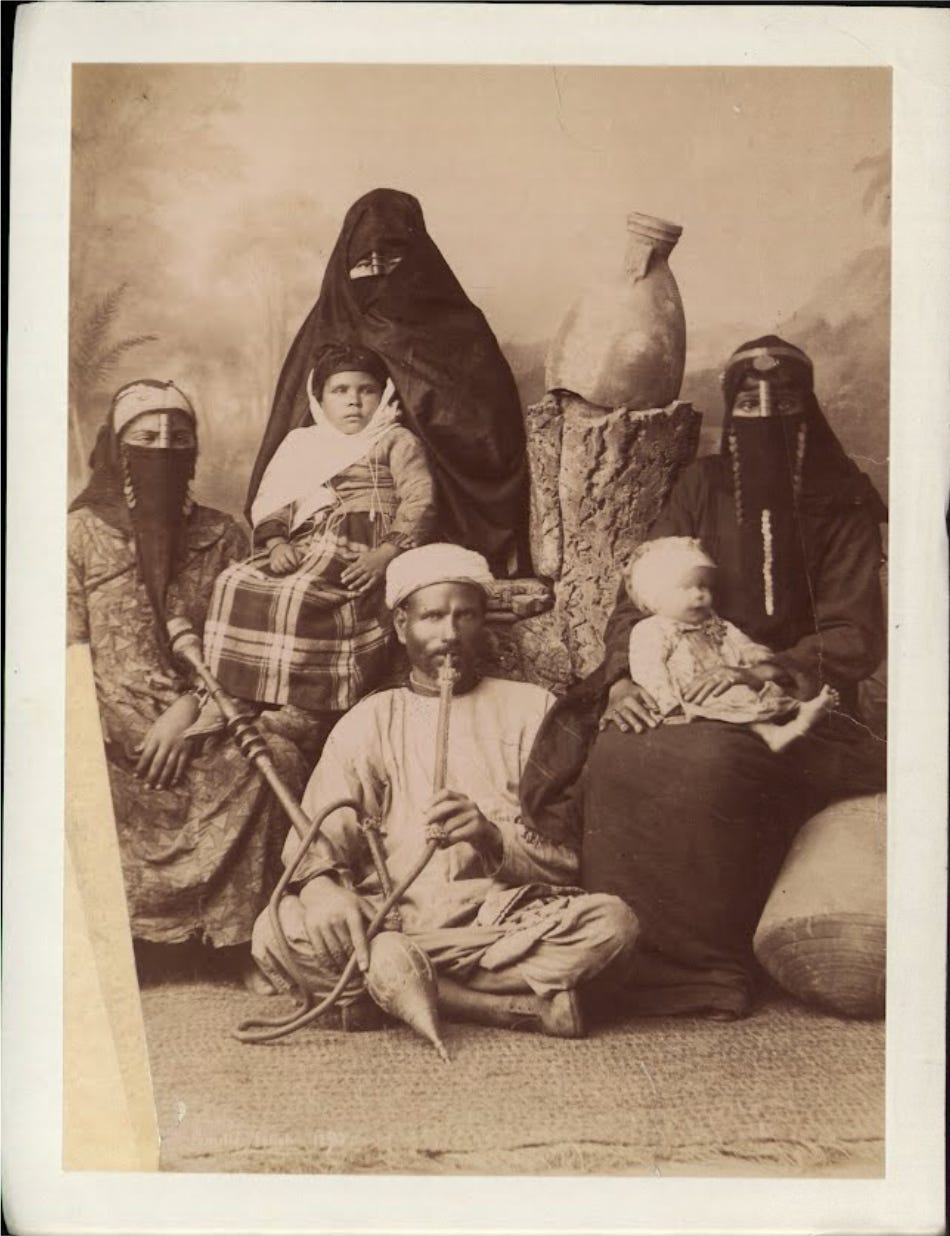

After the Arab conquests, pictures of people in general disappear, and there are no books written by women. With the dawn of photography in the 19th century we see (at left) what was probably typical, veiled women, and very few women on the street.

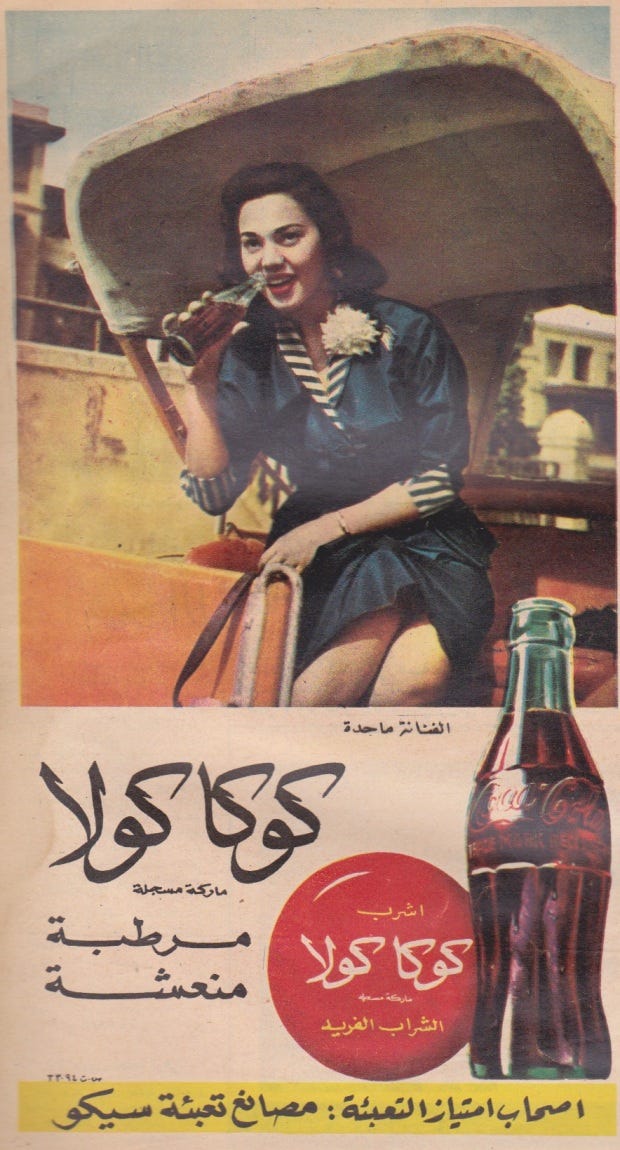

In the 1950s and 1970s we see a remarkable revitalization and liberalization noted most evidently in advertisements (advertisers being careful not to offend). Note the bare legs and the fact that many advertisements are directed at women (below)

This period culminates in a remarkable video unearthed by Evans of Nasser in 1958 openly laughing at the idea that women should or could be required to veil in public. Worth watching.

In the 1980s, however, it all ends.

Egyptians who came of age in the 1950s and ‘60s experienced national independence, social mobility and new economic opportunities. By the 1980s, economic progress was grinding down. Egypt’s purchasing power was plummeting. Middle class families could no longer afford basic goods, nor could the state provide.

As observed by Galal Amin,

“When the economy started to slacken in the early 1980s, accompanied by the fall in oil prices and the resulting decline in work opportunities in the Gulf, many of the aspirations built up in the 1970s were suddenly seen to be unrealistic and intense feelings of frustration followed”.

‘Western modernisation’ became discredited by economic stagnation and defeat by Israel. In Egypt, clerics equated modernity with a rejection of Islam and declared the economic and military failures of the state to be punishments for aping the West. Islamic preachers called on men to restore order and piety (i.e., female seclusion). Frustrated graduates, struggling to find white collar work, found solace in religion, whilst many ordinary people turned to the Muslim Brotherhood for social services and righteous purpose.

That’s just a brief look at a much longer and fascinating post.

Tuesday assorted links

1. A literalist reading of Civil War.

2. Why it is so hard to get a reservation nowadays (New Yorker).

3. “There are currently 682 #AI-related bills (581 of them in the states) on the @MultiStateAssoc legislative tracker.” Link here.

4. The econometrics of social media and mental health. And more on the same. A good piece.

5. Esther Duflo calls for $500 billion in climate reparations (FT).

Hiring discrimination sentences to ponder

Several common measures — like employing a chief diversity officer, offering diversity training or having a diverse board — were not correlated with decreased discrimination in entry-level hiring, the researchers found.

But one thing strongly predicted less discrimination: a centralized H.R. operation.

The researchers recorded the voice mail messages that the fake applicants received. When a company’s calls came from fewer individual phone numbers, suggesting that they were originating from a central office, there tended to be less bias. When they came from individual hiring managers at local stores or warehouses, there was more. These messages often sounded frantic and informal, asking if an applicant could start the next day, for example.

“That’s when implicit biases kick in,” Professor Kline said. A more formalized hiring process helps overcome this, he said: “Just thinking about things, which steps to take, having to run something by someone for approval, can be quite important in mitigating bias.”

Seasonality and the Invention of Agriculture

Forthcoming from the QJE, here is a new paper by Andrea Matanga:

The Neolithic revolution saw the independent development of agriculture among at least seven unconnected hunter-gatherer populations. I propose that the rapid spread of agricultural techniques resulted from increased climatic seasonality causing hunter-gatherers to adopt a sedentary lifestyle and store food for the season of scarcity. Their newfound sedentary lifestyle and storage habits facilitated the invention of agriculture. I present a model and support it with global climate data and Neolithic adoption dates, showing that higher seasonality increased the likelihood of agriculture’s invention and its speed of adoption by neighbors. This study suggests that seasonality patterns played a dominant role in determining our species’ transition to farming.

Here are various less gated copies. Via Nicanor Angle.

Monday assorted links

1. Are Indian women stronger relative supporters of Modi?

2. Apple to build on-device AI?

3. The remarkable economic recovery of Sri Lanka?.

4. “UK alcohol-related deaths up one-third on pre-pandemic levels…” (FT)

5. New Cass Sunstein book on campus free speech.

6. The Straussian approach to the new Taylor Swift.

7. Macro Musings podcast from Mercatus is now powered by AI.

Deregulate our universities

Take a look at how the number of federal regulations and policies governing research at universities has dramatically increased over the years.

This adding an enormous cost of doing research.

(Source COGR) pic.twitter.com/ezqAsLUIIj

— Denis Wirtz (@deniswirtz) April 20, 2024

Via Matt Yglesias.

Tying the Knot

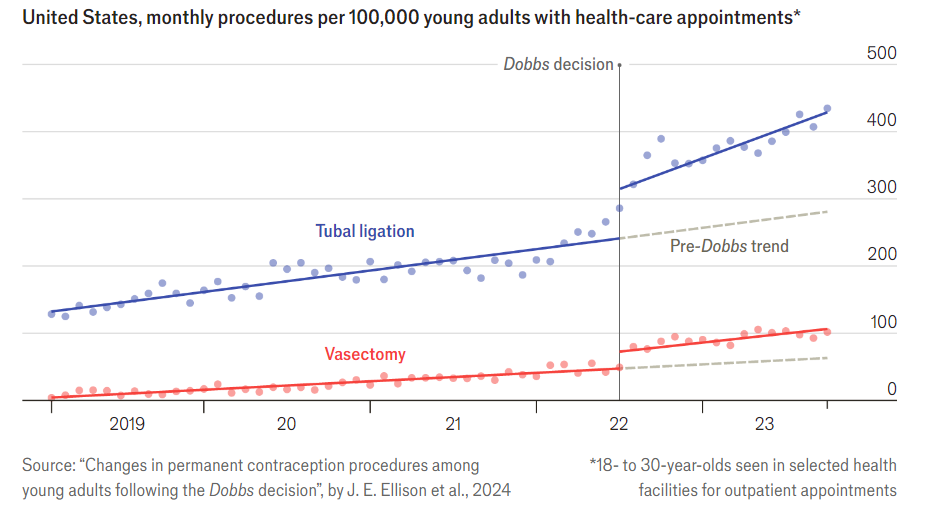

Dobbs, of course, was the Supreme Court decision saying that the constitution does not provide a right to abortion, thus leading to restrictions on abortion in many states. The pictures is from The Economist, the original paper is here.

Arguments that (almost) everyone hates

These are usually worth pondering, as at the very least you will learn something. Here is a hate-worthy paragraph from an earlier Bloomberg column of mine:

…note that higher real estate prices, to the extent they result from immigrant demands, largely translate into capital gains for homeowners — most of whom are native-born. To be sure, the higher home prices may be bad for many younger Canadians, who may be locked out of housing markets, but eventually many of them will inherit high-valued homes from their parents.

Yet it is true. “Immigrants pushing up home prices” should not be a major worry, though it does create some distributional problems (is this the main way to induce conservatives to worry about distributional problems?).

With some effort maybe one can make the dislike of the argument stronger. Often I hear “Oh, it’s good if we taken in lots of immigrants. But the more that come, the more we need YIMBY to house them at reasonable expense.”

Maybe! But let’s not forget the terms of trade models for international exchanges. If one of our export industries is “selling homes to arriving foreigners,” you might want your sellers to collude, restrict output, and raise prices to the foreigners. At least if you are maximizing the welfare of initial natives.

And that is precisely what NIMBY policies do, namely by enforcing a kind of implicit collusion, they force the arrivals to pay more for homes. Pay more to the natives, that is.

Raise your hand if you’re against capital gains!

Of course the cosmopolitans amongst us can resolve these issues rather easily.

Guinea pig questions

If someone demographically normal and not especially at-risk wants to serve as a guinea pig, what is the optimal allocation of that resource?

Is there any formal discussion of this question? I know they say “there is always an Effective Altruism blog post,” but is there?

Mostly I have medicine and medical experimentation in mind, but I can imagine other answers as well, such as “trying to leap forty flaming cars with a motorcycle.” Though I doubt that one will end up as the winner. In any case, I am assuming away legal constraints. Where can you volunteer as a guinea pig for the highest social value?

Sunday assorted links

1. Rasheed Griffith reggae playlist.

2. Poland got rid of compulsory homework for grade school.

3. Suicide rate trends for German teen females.

4. Important job ad for finding and cultivating talent in Brazil, no Portuguese required.

6. Claims about microwave missiles, speculative.

The game theory of the final round of the Candidates

The amazing Gukesh (17 years old!) is half a point ahead with one round remaining today. Three players — Nakamura, Caruana, and Nepo — trail him by half a point. Naka is playing Gukesh, and of course Naka will try to win. But what about Caruana vs. Nepo? Yes, each must try to win (no real reward for second place), but which openings should they aim for? You might think they both will steer the game in the direction of freewheeling, risky openings. Game theory, however, points one’s attention in a different direction. What if one of the two players opts for something truly drawish, say like the Petroff or (these days) the Berlin, or the Slav exchange variation? Then the other player really needs to try to win, and to take some crazy chances in what is otherwise a quite even position. Why not precommit to “drawish,” knowing the other player will have to go to extreme lengths to rebel against that?

Of course game theory probably is wrong in this case, but is this such a crazy notion? I’ll guess we’ll find out at about 2:45 EST today.

What should I ask Alan Taylor?

He is one of the greatest of living American historians, here is from Wikipedia:

Alan Shaw Taylor (born June 17, 1955) is an American historian and scholar who is the Thomas Jefferson Memorial Foundation Professor of History at the University of Virginia. A specialist in the early history of the United States, Taylor has written extensively about the colonial history of the United States, the American Revolution and the early American Republic. Taylor has received two Pulitzer Prizes and the Bancroft Prize, and was also a finalist for the National Book Award for non-fiction.

He has a new and excellent book out, namely American Civil Wars: A Continental History 1850-1873. Among his other virtues, he is renowned for tying in American history to developments in Canada, Mexico, and the Caribbean. So what should I ask him?

“The Simple Macroeconomics of AI”

That is the new Daron Acemoglu paper, and he is skeptical about its overall economic effects. Here is part of the abstract:

Using existing estimates on exposure to AI and productivity improvements at the task level, these macroeconomic effects appear nontrivial but modest—no more than a 0.71% increase in total factor productivity over 10 years. The paper then argues that even these estimates could be exaggerated, because early evidence is from easy-to-learn tasks, whereas some of the future effects will come from hard-to-learn tasks, where there are many context-dependent factors affecting decision-making and no objective outcome measures from which to learn successful performance. Consequently, predicted TFP gains over the next 10 years are even more modest and are predicted to be less than 0.55%.

Note he is not suggesting TFP (total factor productivity, a measure of innovation) will go up by 0.71 percentage points (a plausible estimate, in my view), he is saying it will go up 0.71% over a ten year period, or by 0.07 annually. Here is the explanation of method:

I show that when AI’s microeconomic effects are driven by cost savings (equivalently, productivity improvements) at the task level—due to either automation or task complementarities—its macroeconomic consequences will be given by a version of Hulten’s theorem: GDP and aggregate productivity gains can be estimated by what fraction of tasks are impacted and average task-level cost savings. This equation disciplines any GDP and productivity effects from AI. Despite its simplicity, applying this equation is far from trivial, because there is huge uncertainty about which tasks will be automated or complemented, and what the cost savings will be.

Mostly I think this piece is wrong, and I think it is wrong for reasons of economics. It is not that I think the estimate is off, I think the method is misleading altogether.

As with international trade, a lot of the benefits of AI will come from getting rid of the least productive firms from within the distribution. This factor is never considered.

And as with international trade, a lot of the benefits of AI will come from “new goods,” Since the prices of those new goods previously were infinity (do note the degree of substability matters), those gains can be much higher than what we get from incremental productivity improvements. The very popular Character.ai is already one such new good, not to mention I and many others enjoy playing around with LLMs just about every day.

By the way, the core model of this paper — see pp.6-7 — postulates only a single good for the economy. Mention of the contrary case does surface on p.11, and starting with p.19, where most of the attention is devoted to bad new goods, such as more effective manipulation of consumers. Note the paper doesn’t have any empirical argument as to why most new AI goods might be bad for social welfare.

pp.34-35 focus on the possibility of a public goods problem for AI use, similar to what has been suggested for social media. That discussion seems very far from both current practices with AI and most of the speculation from AI experts. Do I have to use Midjourney because all of my friends do, and I wish the whole thing didn’t exist? Or rather do I simply find it to be great fun, as do many people when they create their own songs with AI? It is dubious to play up the prisoner’s dilemma effects so much, but Acemoglu returns to this point with much force in the conclusion.

Toward the end he writes:

Productivity improvements from new tasks are not incorporated into my estimates. This is for three reasons. First and most parochially, this is much harder to measure and is not included in the types of exposure considered in Eloundou et al. (2023) and Svanberg et al. (2024). Second, and more importantly, I believe it is right not to include these in the likely macroeconomic effects, because these are not the areas receiving attention from the industry at the moment, as also argued in Acemoglu (2021), Acemoglu and Restrepo (2020b) and Acemoglu and Johnson (2023). Rather, areas of priority for the tech industry appear to be around automation and online monetization, such as through search or social media digital ads. Third, and relatedly, more beneficial outcomes may require new institutions, policies and regulations, as also suggested in Acemoglu and Johnson (2023) and Acemoglu et al. (2023).

While many of the points in that paragraph seem outright wrong to me (such as the industry attention point), what he can’t bring himself to say is that the gains from such new tasks will in fact be small. Because they won’t be. But whether or not you agree, what is going on in the paper is that the gains from AI measure as small because it is assumed AI will not be doing new things. I just don’t see why it is worth doing such an exercise.

A more general question is whether this model can predict that TFP moves around as much as it does. I am pretty sure the answer there is “no,” not anywhere close to that.

On the general approach, I found this sentence (p.4) very odd: “…my framework also clarifies that what is relevant for consumer welfare is TFP, rather than GDP, since the additional investment comes out of consumption.” I would say what is relevant for consumer welfare is the sum of consumer and producer surpluses, of which TFP is not a sufficient statistic. This unusual “redefinition of all welfare economics in a single sentence” perhaps follows from how many other gains from trade he has abolished from the system? And footnote six is odd and also wrong: “For example, if AI models continue to increase their energy requirements, this would contribute to measured GDP, but would not be a beneficial change for welfare.” Even for dirty energy that might be wrong, not to mention for green energy. If an innovation induces the market to invest more in a service, the costs of that added investment simply do not scuttle the gains altogether. And if Acemoglu wants to argue that weird welfare economics is true in his model, that is a good argument against his model, not a good argument that such gains would not count in the real world, which is what this paper is supposed to be about.

Acemoglu explicitly rules out gains from doing better science, as they may not come within the ten-year time frame. On that one, he is the prisoner of his own assumptions. If many gains come in say years 10-15, I would just say the paper is misleading, even if his words are defensible in the purely literal sense.

That said, just how much does the “no new science” clause rule out? In terms of an economic model, how does “new science” differ from “TFP”? I am not sure, not are we given clear guidance. Is better software engineering “new science”? Maybe so? Won’t we get a lot of that within ten years? Don’t we have some of it already?

In sum, I don’t think this paper at all establishes the “small gains point” it is trying to promote in the abstract.

It is perfectly fair to point out that the optimists have not shown large gains, but in this paper the deck is entirely — and unfairly — stacked in the opposite direction.

For the pointer I thank Gabriel.

South Africa fact of the day

Two economists from the Harvard Growth Lab (Shah and Sturzenegger) estimate that the average transport costs for those who are employed in South Africa is equal to 57% of net wages when time to commute is accounted for.

Here is the whole John McDermott tweet storm, in part that is the spatial legacy from the earlier system of apartheid, and in part from poor public transport systems. Here is a related blog post.