Today I will write about recent comics by French artists in furtherance of my election campaign for President of the United States of America.

-Robert F. Kennedy Jr.

* * *

Social Fiction by Chantal Montellier, translated by Geoffrey Brock, re-lettered by Dean Sudarsky; published by New York Review Comics

When people used to talk about Métal hurlant, they would include something called the "dirty future" among the magazine's innovations: a vision of the future that is crowded, grimy, overgrown. Often, this would be followed by descriptions of how the aesthetic informed movies like Blade Runner, and don't you know Moebius himself worked on Tron, and etc., with the aim of justifying such aesthetics through its adoption by bigger-gamble art forms.

Montellier was present for the birth of this style, though she did not intend to be. A painter and art teacher who turned to political illustration in the early '70s, she made her way into longer, narrative comics in Charlie mensuel in 1974, then Ah! Nana—a sibling magazine to the young Métal, inspired by women-led American undergrounds like Wimmen's Comix—in 1976, at the behest of editorial secretary Anne Delobel, who was a collaborator of Jacques Tardi. But while much of Montellier's energy became focused on Ah! Nana, she also contributed small, linked pieces to Métal: her first such comic, the debut installment of her 1996, appeared in Métal hurlant #7 (May 1976), alongside the first chapter of Moebius' & Dan O'Bannon's "The Long Tomorrow", the comic that popularized the proto-cyberpunk style in its winking blend of detective noir clichés and droll SF devices, its femme fatale a literal monster of devouring feminine desire. But it was the appetites of Ah! Nana that proved concerning to the sweet eyes of France; it was prohibited for sale to minors, which meant it could not be displayed on newsstands, which meant its circulation dropped hard, which meant it became, after nine issues, financially unviable. So Montellier's serial work moved to Métal.

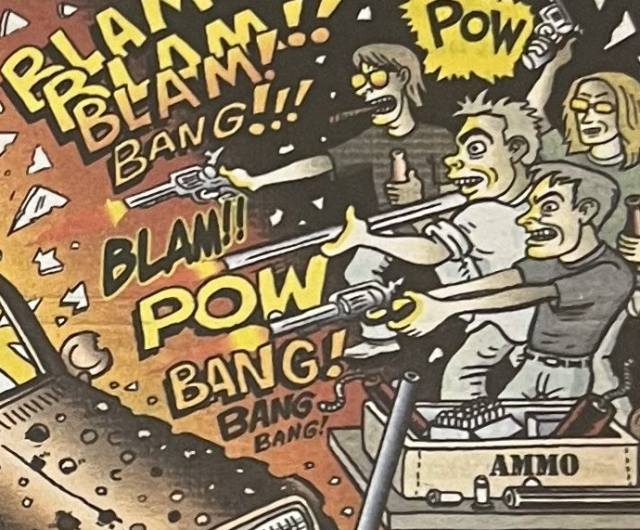

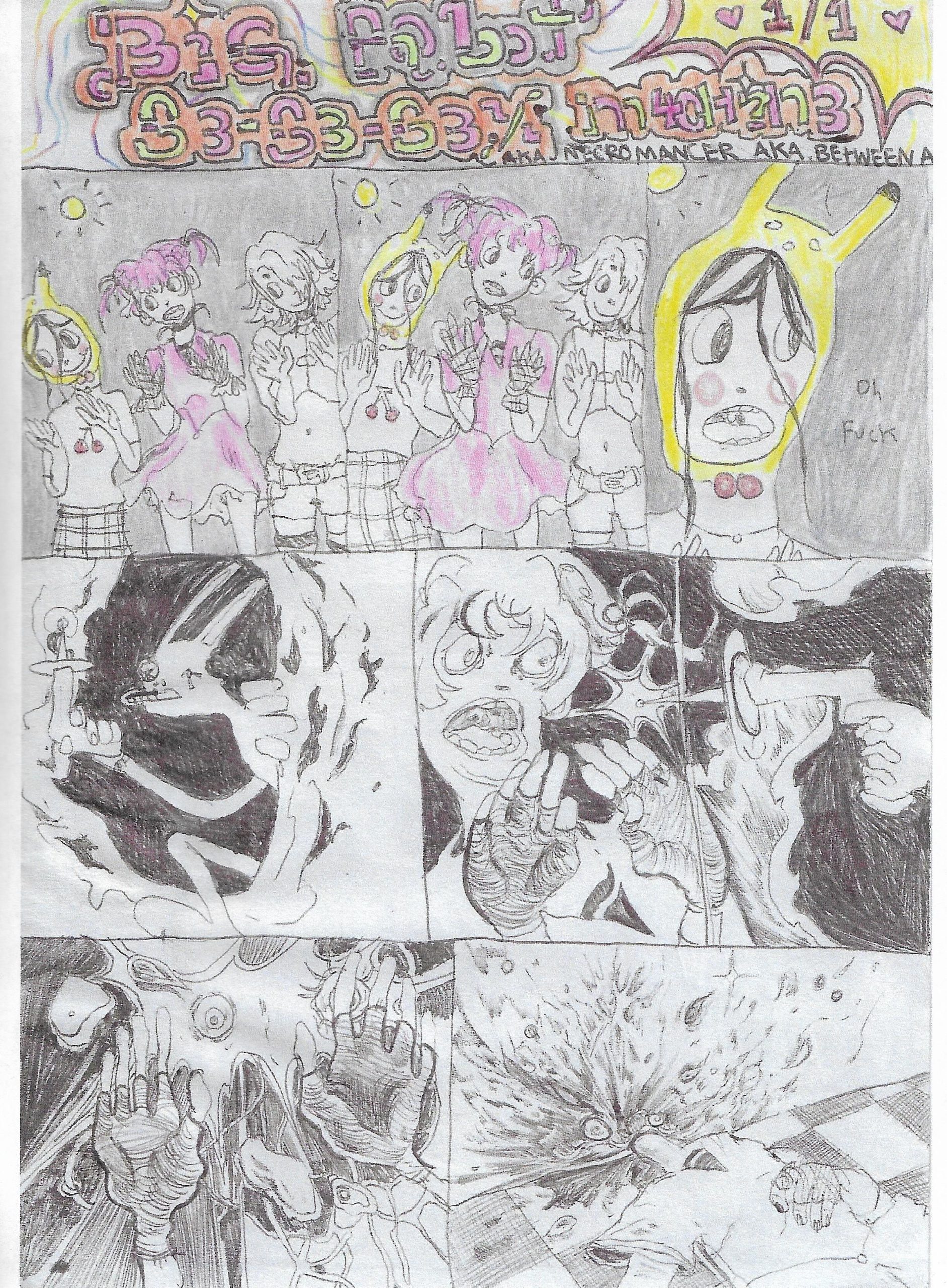

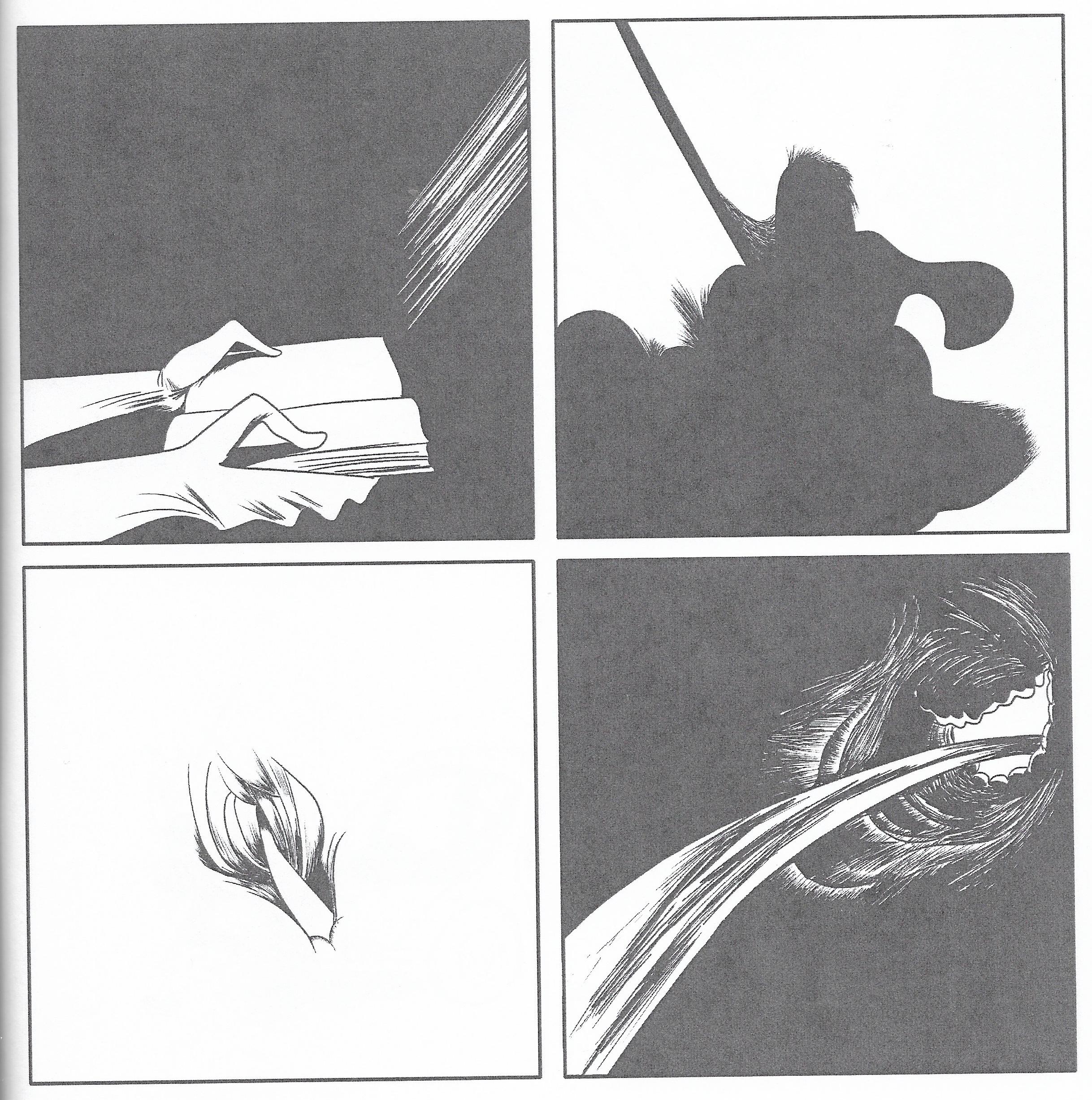

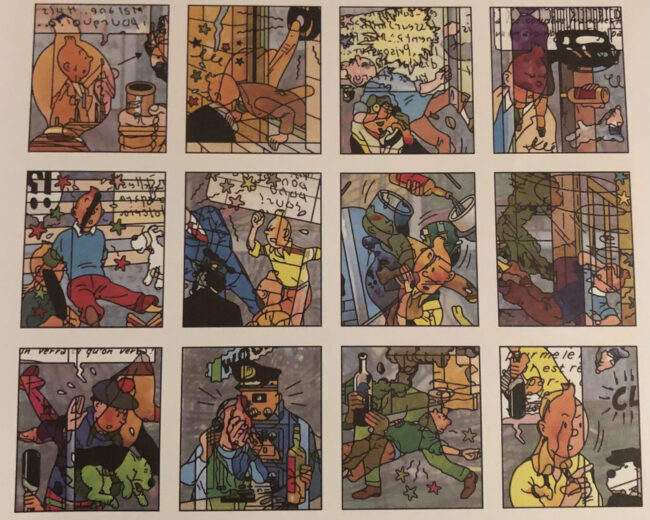

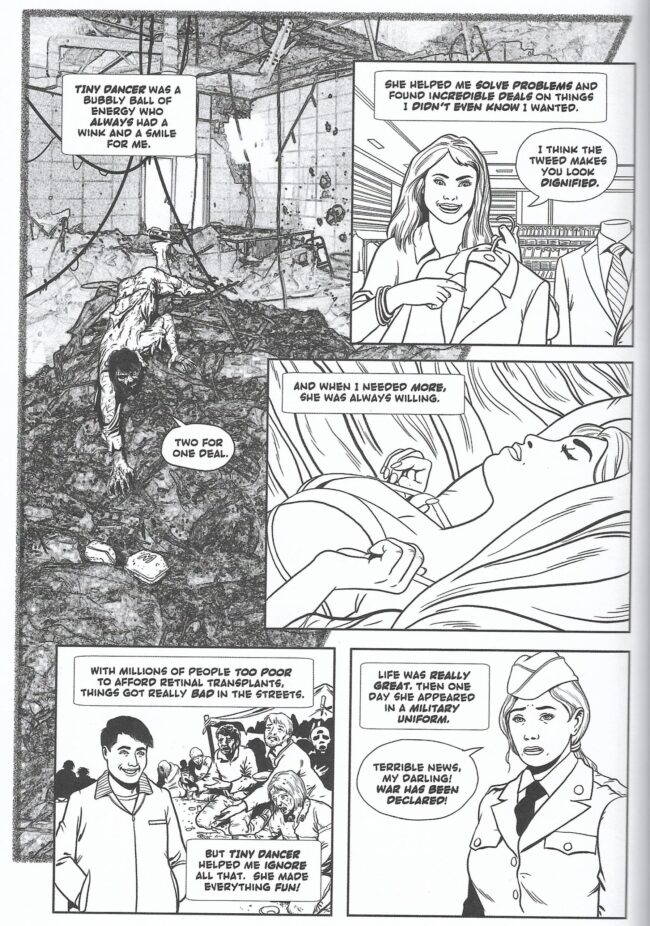

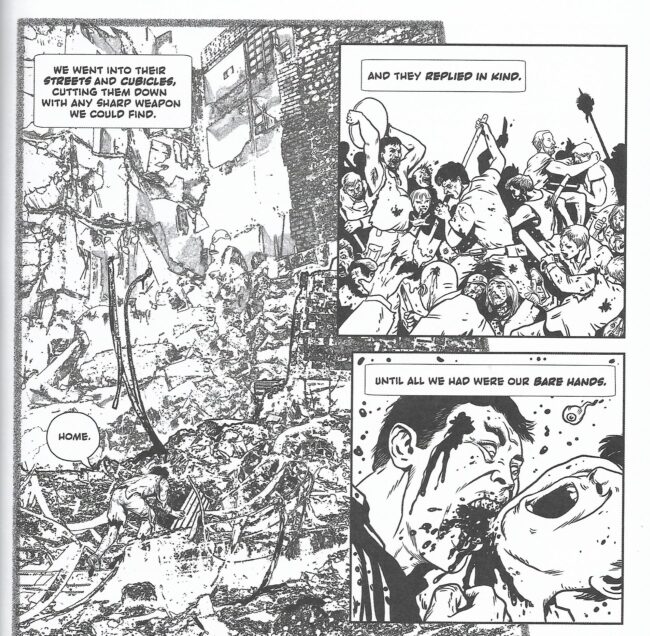

It is always striking to encounter Montellier in Métal hurlant, or the American Heavy Metal magazine, which ran her work throughout its first two and a half years. In a sea of rich color and dense ink, one is suddenly alone on a glacier. Her comics are eerie and still—even when depicting motion, one is aware from the page that everything is still—incidentally resembling Tardi, or Chester Gould sometimes, but Montellier has sealed these men in plastic and beckons you to look, look at them: her comics are discursive, her figures less inhabitants of space than collaged figures. See the heap of bodies above: a civilization of comic strips piled as cultural refuse in the cellar of an art gallery-cum-automobile dealership just 10 years from now. Later, she would become far more overt about clipping isolated images and digitally pasting them into arrangements on the page, less realistic than iconographic, analytic, but here she still observes the traditions of narrative strip art.

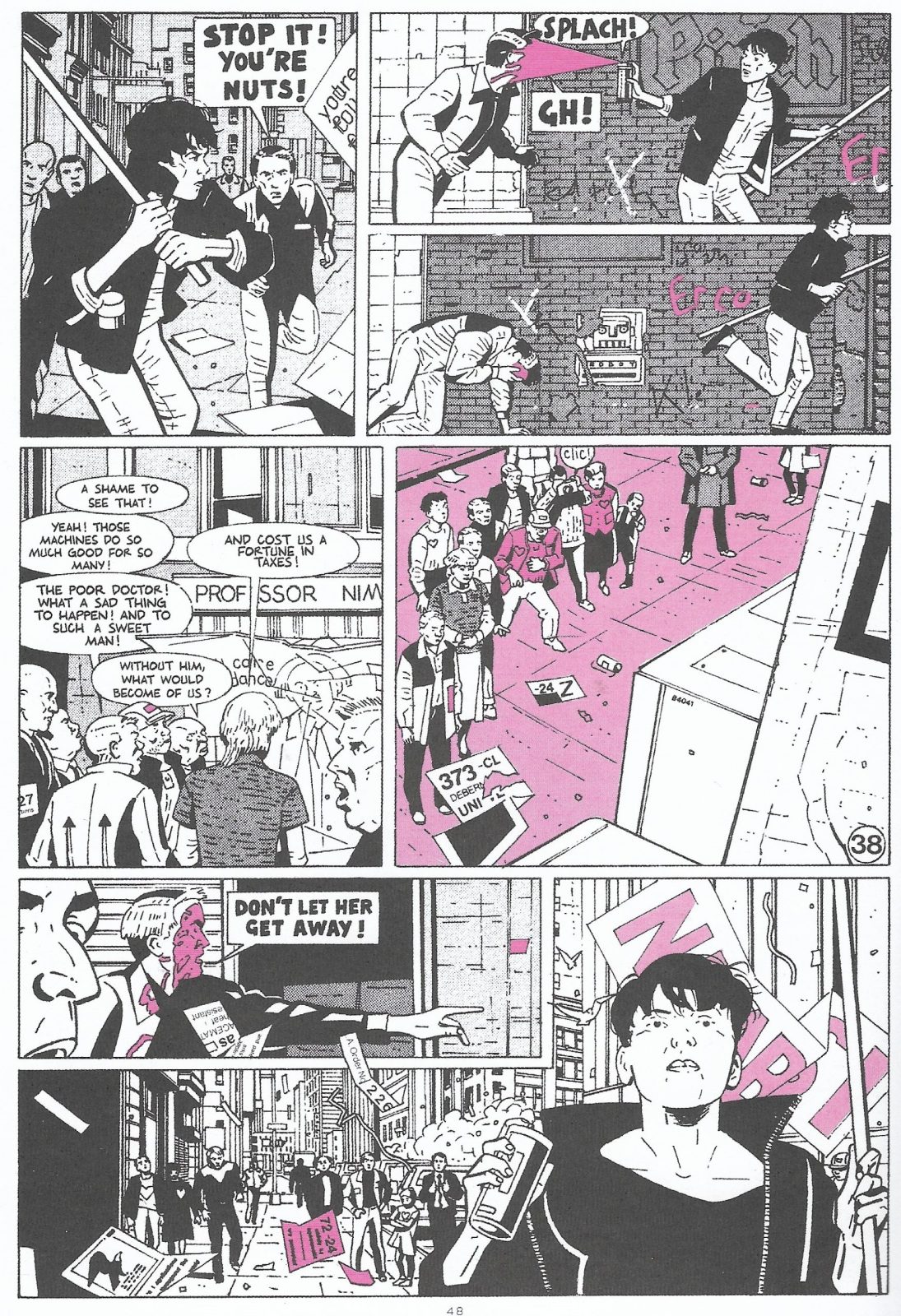

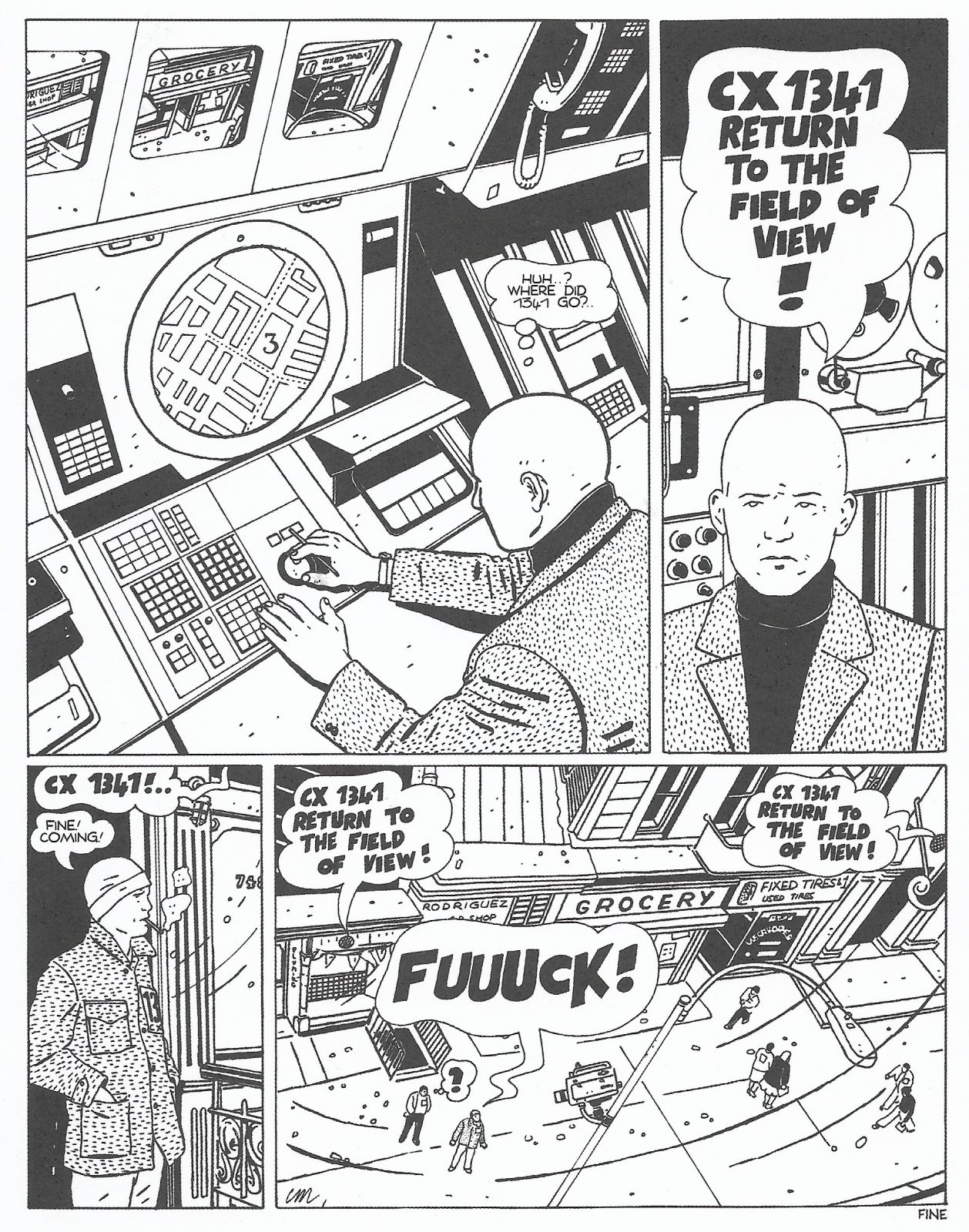

Social Fiction, published just now by NYRC, collects three of Montellier's serial albums from Métal hurlant: the aforementioned 1996 (1976-78); Shelter (1978-79); and Wonder City (1982). Specifically, they are revised versions of those albums, sometimes significant re-drawn, and, in the case of Wonder City, also re-colored. That said, the comics appear to be the same as presented in the 2003 Vertige Graphic edition of this material in French, so it's been 20 years since the stuff has been touched. (The NYRC edition also repeats a certain fuzziness to some images from the Vertige Graphic edition, which I fear may be owing to the state of the materials.) For readers of a certain age, 1996 will be immediately memorable as a puzzling feature of those early Heavy Metals, if in part due to a localization strategy by which much of the dialogue is spelled out as phonetic sounds: LEE MEEYULONE! YU GOD NO RIDE! It later emerges that everyone in the comic is being forced into surgery, in part, to correct this indigenous (or, as is suggested at one point, nuclear fallout-related) dialect so that they conform to 'correct' comic book lettering - thus imposing an editorial subplot onto Montellier's comic, which contained no such element in French. Those editors, Sean Kelly & Valerie Marchant, were succeeded by Ted White, whose first issue saw the removal of the subsequent Shelter, mid-serialization. This is its first appearance in full English, and the first English translation of the later Wonder City.

But what, you are asking, does it mean to look at comics that look like this? For these three albums, all of them SF, the idea is to observe the broken pieces of the state of the future, and to discern, perhaps, some means of aggravating the cracks in it. Montellier's "dirty future" is not just dirty, it is barely functional. Authority figures constantly make mistakes. Automated systems are filled with blind spots. This is to say, the "dirty future" aesthetic is employed by Montellier to a specific political end. The dystopia in Social Fiction droops from the loosening tape that holds it together, yet people still comply. Like most Métal hurlant contributors, Montellier lived through 1968, but unlike nearly all of them, she worked extensively in radical leftist venues prior to her narrative strip work; the sigh behind her pestilent societies is that of faded promise.

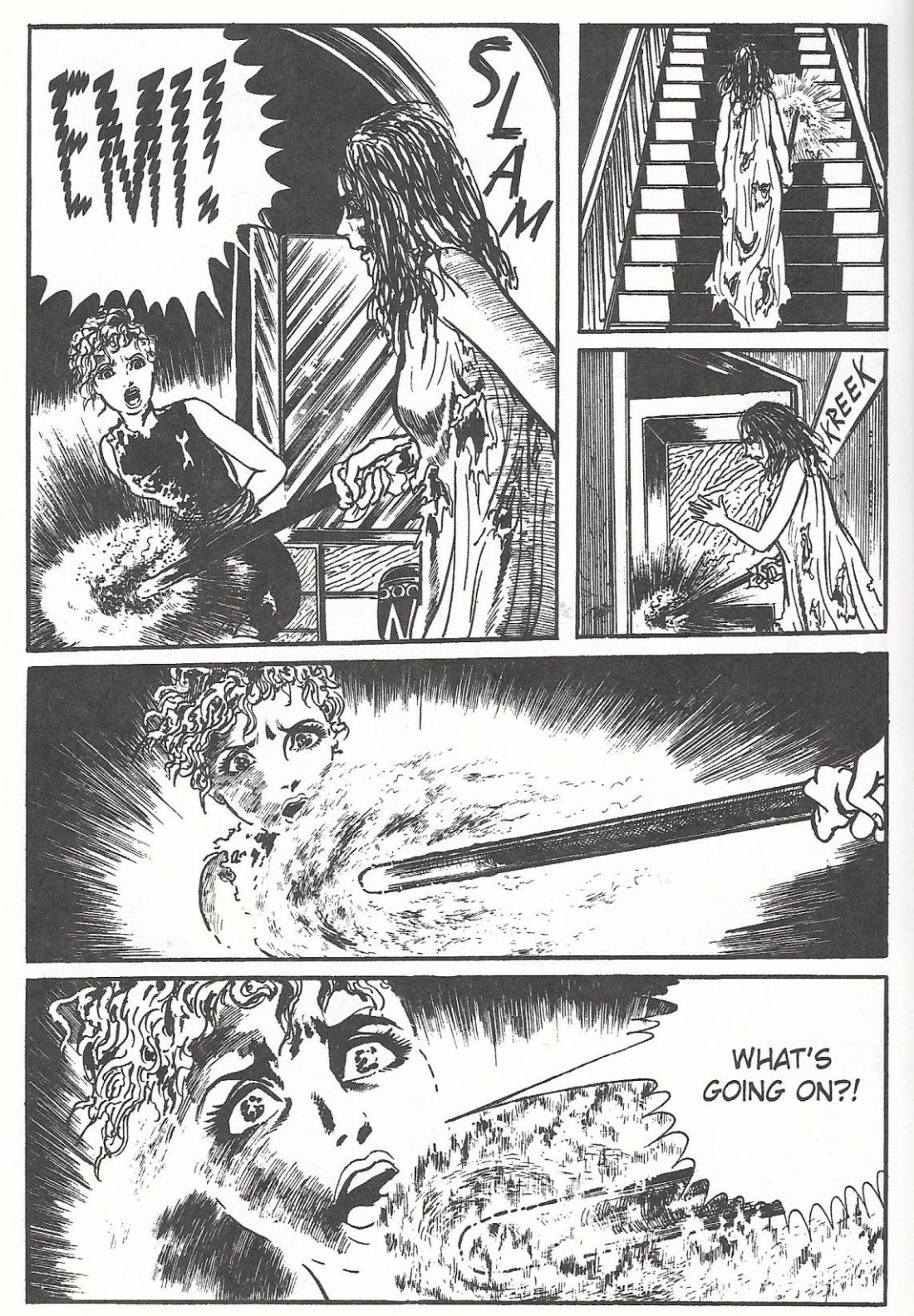

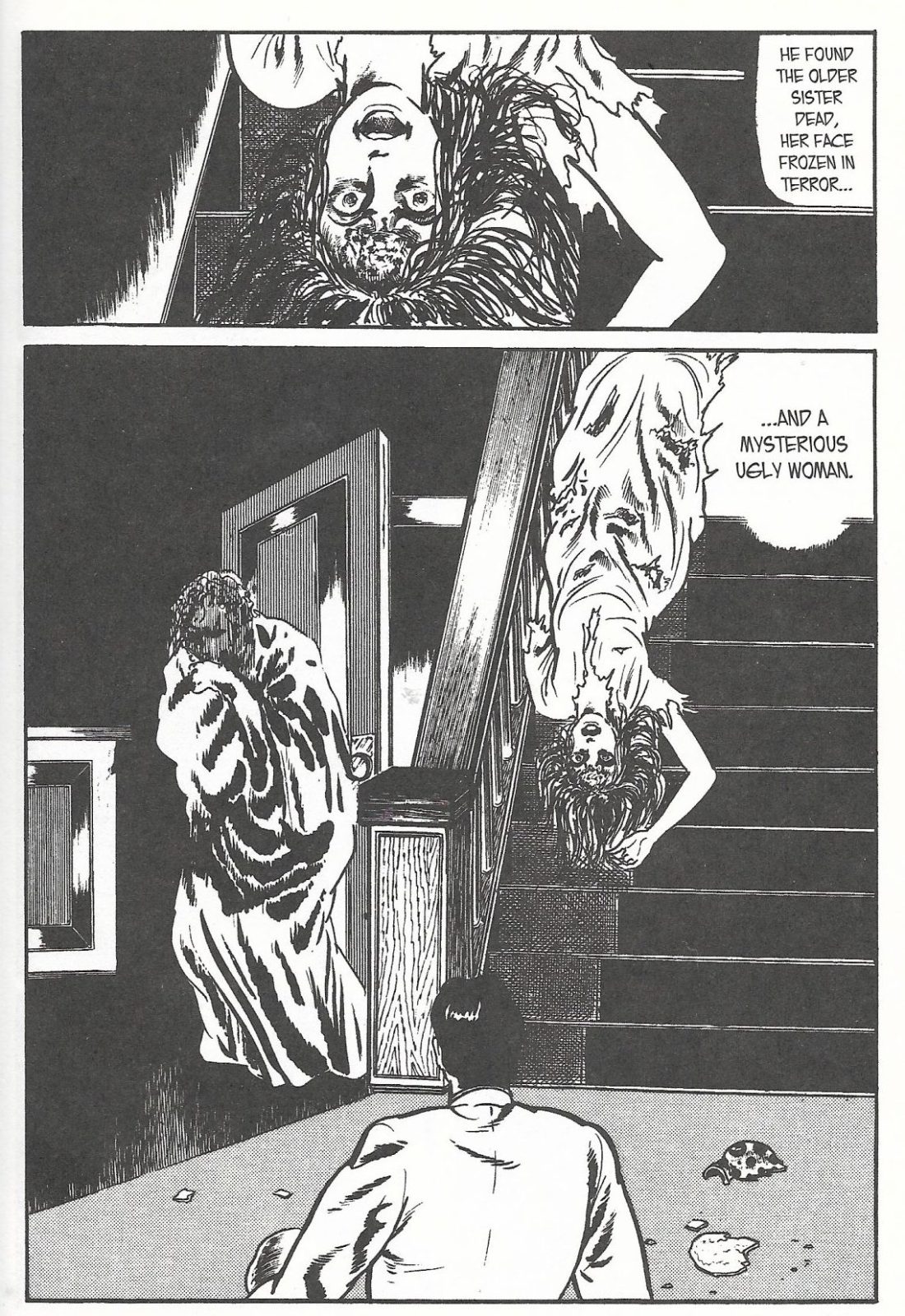

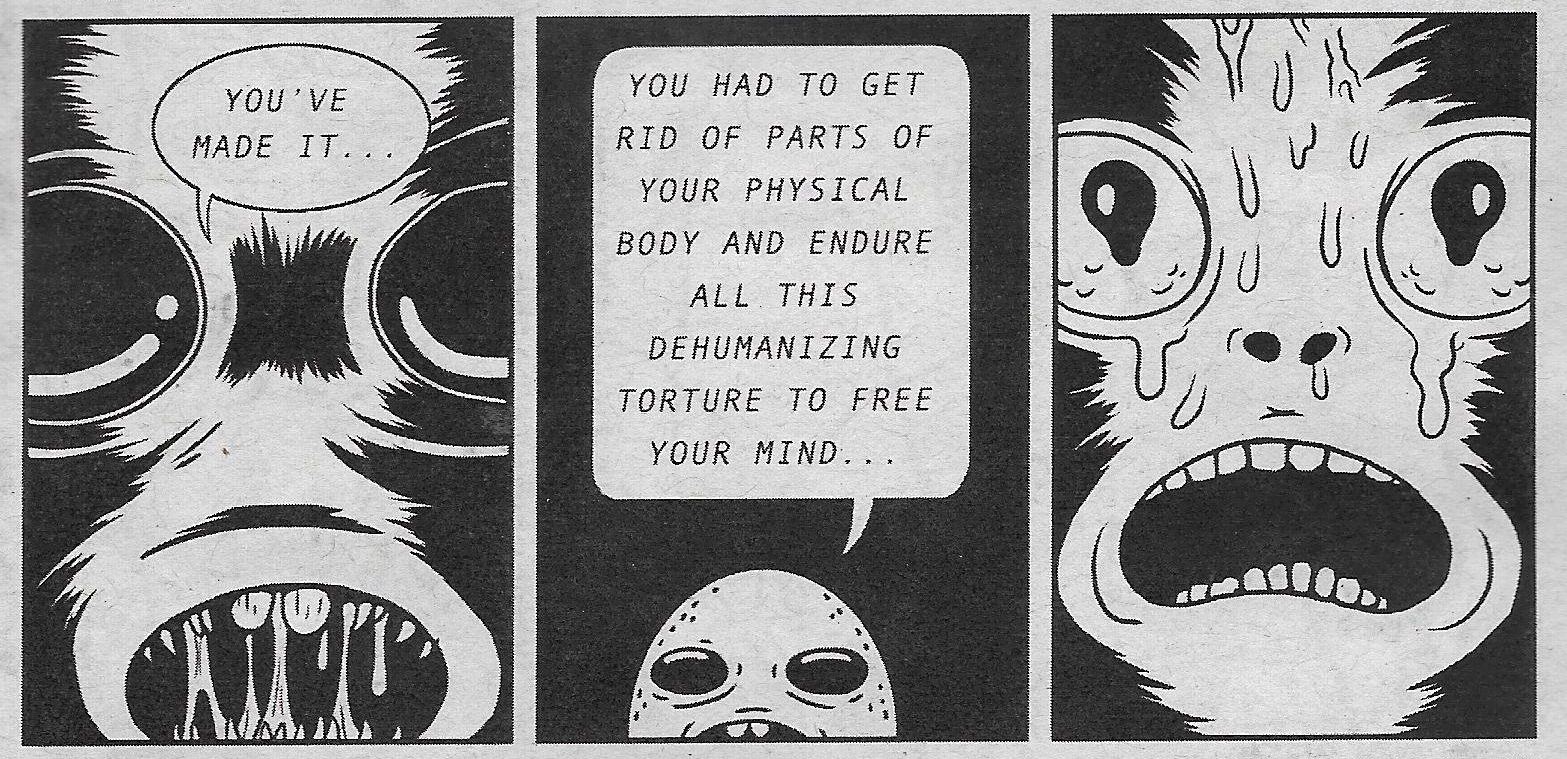

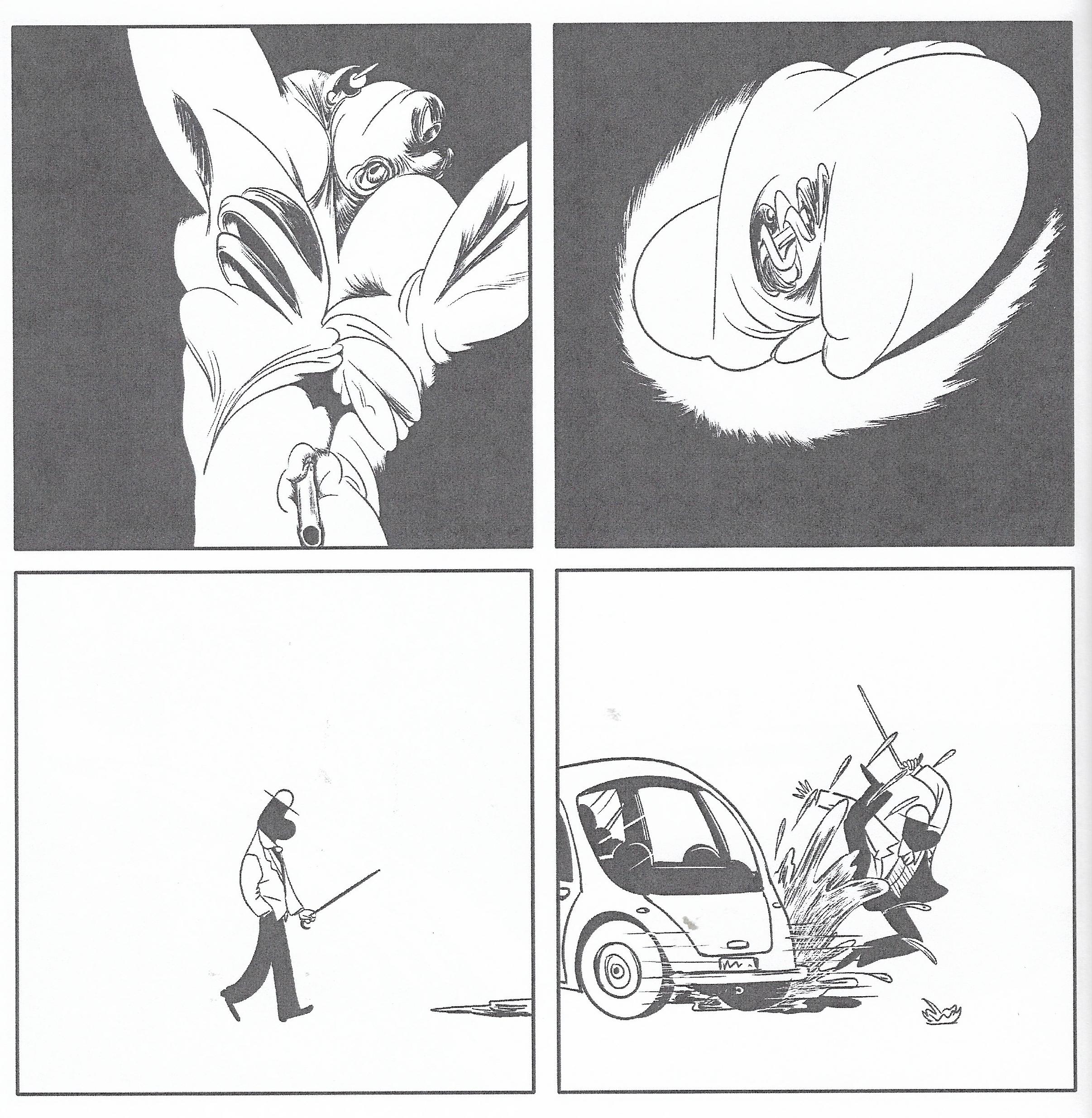

This is information for the observer, with little in the way of an explicit call to action, as I think is expected from writers who chide her for depicting women as victimized by these circumstances. Shelter, especially—in which shoppers are trapped in a massive underground mall, inspired by the Belle Épine shopping center in the Paris suburbs, after a purported nuclear exchange—mordantly tracks the decay of government into totalitarianism; as in Chris Marker's L'Ambassade, another fascism conjured from scraps, an overwhelming sense of dispirit pervades. The heroine, her body at the pleasure of authorities, dreams of herself in a concentration camp that becomes a pornographic fashion show, latex-wrapped flesh as consumable goods. Yet she regrets intensely the costs she imagines her resistance has put on her life. Or, in simpler terms: in one of the vignettes of which 1996 is comprised, a person is walking down the street on a windy day, and is unable to light a cigarette. They duck into a building to get away from the wind. This maneuvers them out of range of the security cameras that purportedly (but do not actually) cover everything. A security professional cries out in frustration, and the smoker, equally annoyed, walks back into range: an obedience dictated by the awkwardness of violating the social contract this surveillance apparatus has drafted. A friend had to explain the joke to me.

Wonder City has a more explicit theme of resistance; a bustling metropolis' AI teledoctor is engaging in eugenics via covert sterilization of undesirable demographics, and a young couple makes a break for it. Among other post-serialization revisions to this album, hair was added to the story's previously bald heroine; the original look was quite close to the characters from George Lucas' 1971 film THX 1138 (speaking of works with several distinct versions), which remains a notable reference. Like not a few French artists, Montellier responds to the stuff of popular genre fiction, so much of it American, with a particular studied gaze.

I think it is very useful that Montellier stands at a certain remove; that these scenes are unsettling and often strange, rather than thrilling. Popular dystopian fiction of this type has a tendency to support one's delusions of superiority; everybody involved in the FTX fraud scandal or the renaming of Twitter to "X" fancy themselves the protagonist of stories like these. There is a very curious undercutting of the lovers' triumph in Wonder City. We dip suddenly inside the characters' heads through a shared thought bubble, and we see they are both thinking in the way a computer thinks. If this is the aptitude that allows them to outthink the eugenicist AI, it is also the subtle victory of the machine; the alteration of human behavior, human thought, to meet the demands of technology. A popular YouTuber speaking in a certain cadence, using certain expressions, to maximize views and profits in a world where prospects are limited; the manner of argument, discourse, controlled by the newest developments in communication platforms. To obey the camera because the camera is there. Montellier is of a generation that is very mindful of this. She remade Shelter, completely, in 2017, as a new album titled Shelter Market—it has not been translated to English, and is not included here—which opens by acknowledging the inspiration of her near-contemporary, the philosopher Jacques Rancière, author of The Politics of Aesthetics. This is one of many routes for future study beyond these brief and very introductory remarks of mine.

L'Almageste by Frédéric Coché, photogravure by Ilan Weiss; published by Frémok

Of any artist that might be read to articulate comics as poetry, Coché is my favorite. He works through metal engraving, for the most part. For a while, he also experimented with oil painting; his 2018 album with Frémok/FRMK, L'homme-armée, sought to combine painted and etched images in an undulating and violent display. Since then, he seems to be sticking to the classic mode. In 2021 he released Brynhildr in conjunction with the scholar Gwladys Le Cuff; they had both completed residencies at La Pommerie, which published the resultant book with Frémok. It pairs a series of Coché etchings and a long critical essay by Le Cuff (in French, mind) on the subject of Wagner's Der Ring des Nibelungen.

L'Almageste now returns Coché to entirely wordless comics.

In fact, L'Almageste reaches back all the way to Coché's first dedicated book, Hortus sanitatis, published in 2000 by the Belgian house Fréon, which would only later combine with the French publisher Amok to form Frémok (which reissued the early album in 2016). Named for a 15th century natural history encyclopedia, Hortus sanitatis saw a knightly Death figure cavort in a city celebration, slaying all he encounters, until he pierces the pregnant belly of a Virgin Mother figure, prompting a vision of a mushroom cloud that becomes a tree grown from a pail of mussels; skeletal Death appears despondent (this too is a wordless comic), wandering contemplatively through a new agrarian city, observing a woman masturbating, and concluding on an enormous penis housed in a chapel at the center of a gigantic fungal patch. This was put together as part of millennial celebrations for the city of Brussels, and places various allusions to Belgian art and culture in comic sequence, the publisher assures.

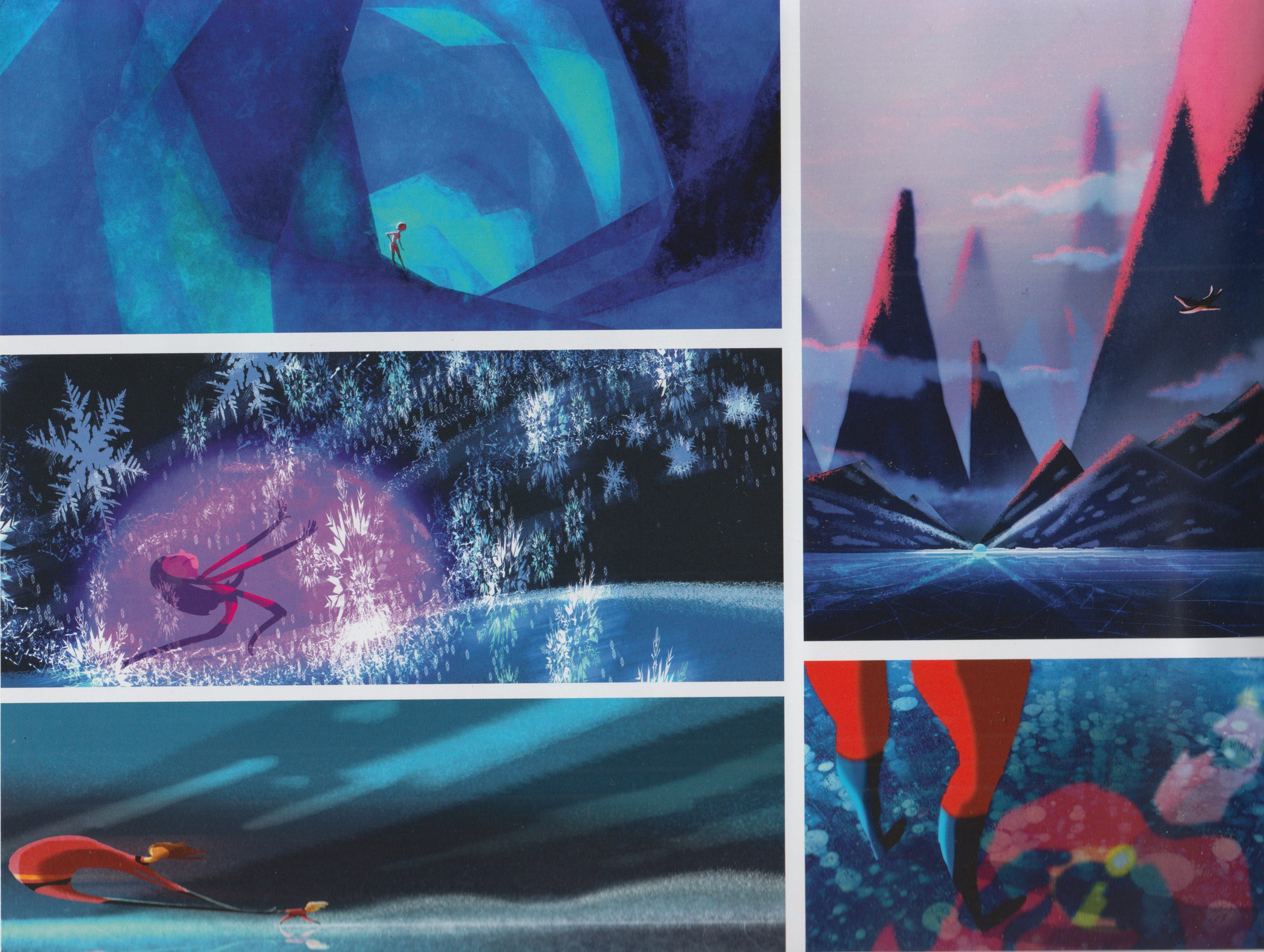

L'Almageste is named for Ptolemy's 2nd century astronomical treatise, and is also concerned with Death and life. One day, nearly every human being in the civilized world wakes up as a skeletal, undead figure. They have apparently forgotten everything about human culture, and set about reconstructing it. Early on, they consider an image of the geocentric astronomical model: the antique manner of viewing the universe outward from the Earth at its center. This is in the midst of the film they are watching of living men in trench warfare, enormous bugs crawling atop them. The undead consider ripping the hearts from the chests of the living and building from them a tower to the heavens, other worlds. An illustrated book and a vinyl record—L'Almageste, incidentally, is Coché's largest, at the square size of an LP sleeve—occasion a fantasy about a heroic angel piercing a maiden, again, with his sword, her body a worm snaking deep down into creation. We imagine, here, Coché's masterpiece, The Hero's Life and Death Triumphant (2005), and wonder uncharitably if this is not a terrific step back. Yet:

L'Almageste is surrounded glimpses of other things. The way the page is arranged, spatially, is that the 'main' activity of the story occurs toward the center gutter of the open book. At each side, like religious panels, are images that do not directly reflect the action, but seem to exist in an allusive or extra-narrative context; some are just parts of drawings, or nests of scratches. Some of these panels seem to be abridgements, cut from larger rectangular pieces, while some are whole. Inherent to Coché's engraved comics is a sense of texture, distress—soot and smudge on the page—but the new idea of this book is emphasize the 'world' of the comic as partially glimpsed from the center of things, like by Earth inhabitants of the geocentric model.

The undead are searching, reforming. They visit a factory where angels bottle people's tears. They drop a coffin into a volcano and it shoots up into the sky and raindrops fall with queens and lutes and bare asses inside, and all the while, as the undead learn themselves to weep, their tears form new skin on their bones. This is a very idealistic, romantic book, in which people feel like they are dead and alienated from everything, and they seek to build a new world from irrational aesthetics. So if we are going back, we are going far, far back, to negate modernity through the historical canon of images in sequence, to become innocent and dead.

It moves and upsets me; both these books do.