The hawkish case

The future course of the economy always involves a bit of guesswork. But it seems to me that the following two claims are pretty likely to be true:

1. Over the past three years, monetary policy has been far too expansionary.

2. It is likely that monetary policy is still a bit too expansionary, although I have less confidence in that claim.

Here are some recent data points, starting with the Financial Times:

A “blowout” March retail sales report sparked a sell-off in US government debt and shook global currency markets on Monday, in the latest sign that the world’s largest economy may be running too hot to justify cutting interest rates.

US retail sales were much stronger than expected in March, as consumers kept spending despite uncertainty about the future path of interest rates. [Note the term “despite”]

Data from the US Census Bureau published on Monday showed that retail sales, which include spending on food and petrol, rose 0.7 per cent last month. Economists surveyed by Reuters had expected an increase of 0.3 per cent.

The figure for February was revised up from a rise of 0.6 per cent to one of 0.9 per cent, indicating resilient consumer spending earlier this year and providing further evidence of a reacceleration of economic growth.

That should read: Reacceleration of nominal economic growth.

Five-year TIPS spreads are back over 2.5%, and rising.

The Atlanta Fed nowcast for real GDP growth is up to 2.8%, implying continued strong nominal growth in Q1. You cannot control inflation without controlling nominal GDP.

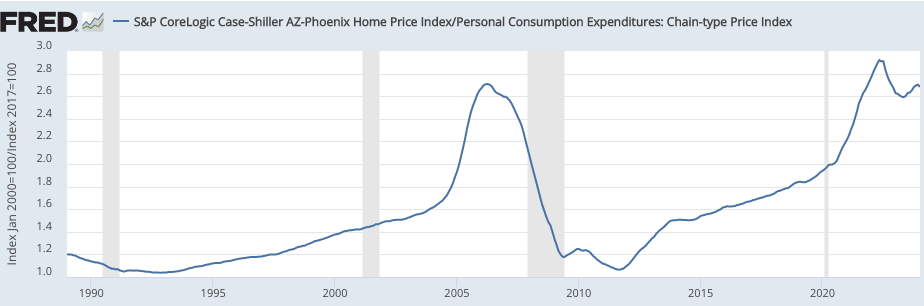

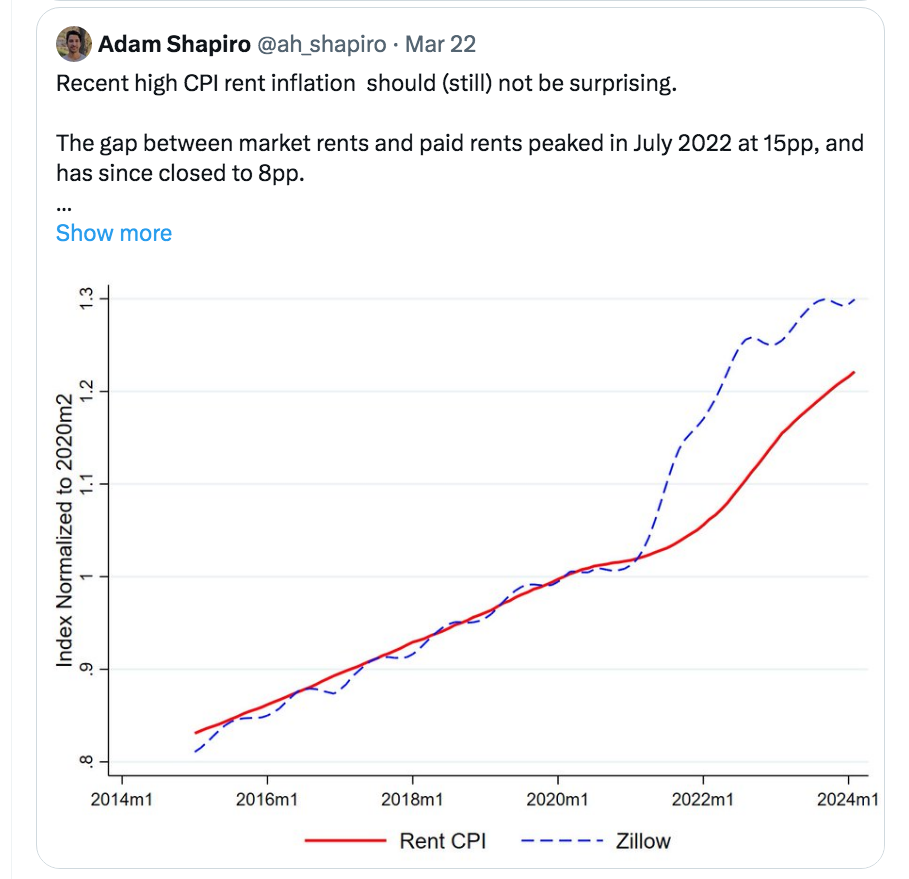

Some people argue that the slowdown in “spot rents” will soon show up in CPI rents. Maybe so, maybe not. It depends on the future course of spot rents, as CPI rents still have a long way to go to catch up with previous increases in spot rents:

If spot rents now begin re-accelerating, then we’ll never get that promised slowdown in CPI rents. Multifamily housing construction is slumping, a bad sign.

I’m not suggesting that inflation cannot slow in the months ahead, as it is impossible to foresee turning points in the economy. Perhaps we’ll be in recession in late 2024. But I do believe the weight of evidence points toward an increased risk of inflation. Given that policy over the previous three years has obviously been way too expansionary, the Fed needs to err on the side of hawkishness (even at the risk of recession.) If you wonder “what’s so bad about 3% inflation”, then you haven’t understood a single thing I’ve said here over the past 15 years.

This is the point where economists discuss “what the Fed should do”, by which they mean where should they set the fed funds target. In my view, interest rates are not the right way to think about monetary policy, so I won’t recommend a particular rate setting. Instead, I’ll recommend making the policy regime more effective.

1. Stop being so clumsy. Right now, the Fed has a psychological aversion to unexpected changes in interest rates. Thus they’d rather not raise rates. But that psychological aversion is irrational, and it makes policy less effective. (I.e., it makes both a recession and an inflation overshoot more likely.) The Fed should adjust their fed funds target daily, to the closest basis point (say using the median vote of FOMC members.) The Fed funds target should look like other market prices, like a random walk. New information should not make people expect a different level of NGDP in 2025, rather new information should show up as the adjustment in the fed funds rate required to keep expected 2025 NGDP on target.

2. Switch to level targeting. The failures of the past three years have many causes, but one factor is of overriding importance. The Fed thinks in terms of growth rates, not levels. That radically increases uncertainty about the future path of NGDP, and largely explains the wild swings in the financial markets in response to seemingly trivial adjustments in Fed policy.

The Fed is not reacting to unexpected swings in aggregate demand, the Fed is creating unexpected swings in aggregate demand, through its clumsy interest rate targeting system and lack of level targeting.